In early October 2020, the Trump administration’s Environmental Protection Agency sent a letter to Oklahoma governor Kevin Stitt. The letter granted Stitt environmental regulatory control over all of the tribal lands in the state. Among other things, this gives Stitt the power to determine whether hazardous waste can be dumped on tribal lands, the ability to make decisions regarding whether and where fracking can take place, and the ability to determine if and where large-scale industrial animal agriculture, with all its attendant pollution, can operate in tribal jurisdictions.

This development is yet another chapter of a disturbing story. In the early to mid-19th century, tribes of indigenous people occupied ancestral lands in states such as Alabama, Florida, Georgia, North Carolina, and Tennessee. These tribes were the Choctaw, Chickasaw, Seminole, Creek, and Cherokee. It didn’t take long for some American whites to realize that the land populated by these tribes was valuable. Many members of the white population had aspirations to attain the land in order to grow cotton on it — cotton that would be picked by African slaves. In 1830, President Andrew Jackson signed the Indian Removal Act, a piece of legislation that allowed congress to “trade” Southern lands with much promise as fertile soil for the growth of cotton for “Indian colonization” lands across the Mississippi River. What these trades meant in practice was that native populations were relocated from their ancestral lands to places to which they had no connections. In many cases they were removed from their lands forcibly. They were not provided with supplies or support on their journey to their new home. The path was long and treacherous, and many native travelers did not survive. The procession came to be known as the “Trail of Tears.”

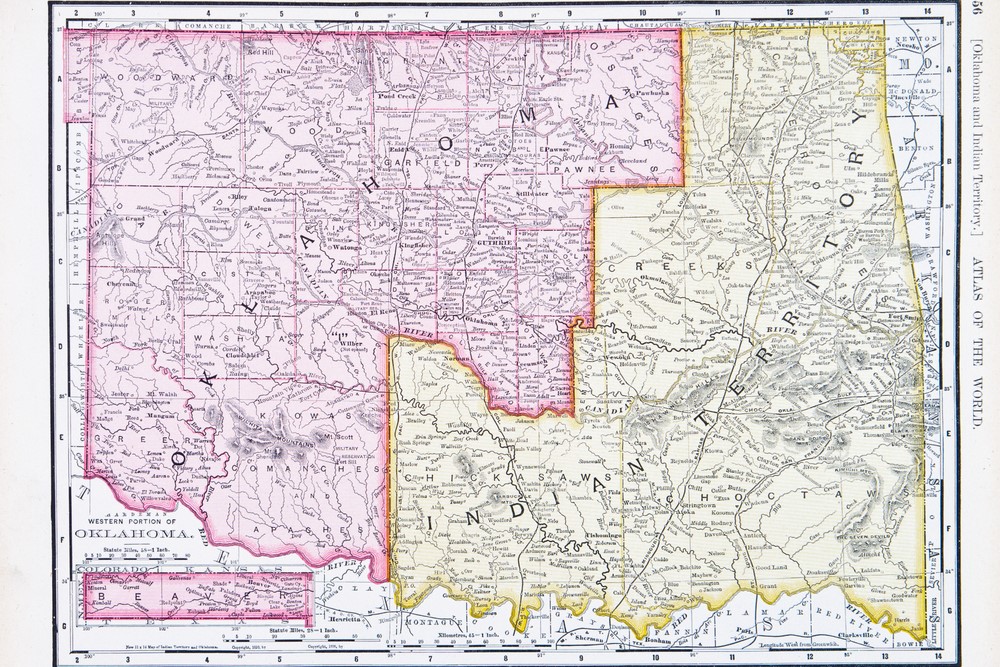

Some of the members of the five tribes that survived this journey settled in reservation lands in eastern Oklahoma, which at the time was not a state. The tribal land comprised a significant portion of what is now the state. In many respects, in recent years the government of Oklahoma has increasingly treated native persons as if they have no rights over their own lands. Many people in power in the region are of the opinion that the reservation status of the eastern part of the state was disestablished in 1907 when Oklahoma was admitted into the union. The state has argued that the disestablishment occurred during the “allotment” process, when the land was divided up and treated as individually owned by members of the respective tribes.

The question of whether Five Tribes reservations had been disestablished was resolved by the United States Supreme Court in July 2020. Two cases generated the controversy. In one case, Patrick Murphy, a member of the Creek Nation, was accused of committing a murder. He was convicted and sentenced by the state of Oklahoma. If native persons live on federal reservations, they are subject only to tribal and federal law. Murphy contended that he was tried in the wrong jurisdiction — he should have been tried not by the state but by the federal government. The second case was a case in which Jimcy McGirt was tried and convicted by the State of Oklahoma. He was given two sentences of 500 years for raping a four-year-old girl. On appeal, counsel for McGirt argued that, because the crime took place on the soil of the reservation, McGirt, too, was sentenced in the wrong jurisdiction. Representatives of the State of Oklahoma contended that the lands occupied by the Five Tribes are no longer established reservations. The Supreme Court disagreed, finding no evidence that reservation status had at any time been revoked. Writing for the majority, Justice Gorsuch said,

“The federal government promised the Creek a reservation in perpetuity. Over time, Congress has diminished that reservation. It has sometimes restricted and other times expanded the tribe’s authority. But Congress has never withdrawn the promised reservation. As a result, many of the arguments before us today follow a sadly familiar pattern. Yes, promises were made, but the price of keeping them has become too great, so now we should just cast a blind eye. We reject that thinking. If Congress wishes to withdraw its promises, it must say so. Unlawful acts, performed long enough and with sufficient vigor, are never enough to amend the law. To hold otherwise would be to elevate the most brazen and longstanding injustices over the law, both rewarding wrong and failing those in the right.”

News agencies reported this opinion as a “landmark decision” by the Supreme Court. The opinion acknowledged the historic and continued injustice endured by members of these tribes and it demanded that the government keep its promises. In the wake of the decision, many speculated that tribal members would have more of a voice in decisions about the environment as it relates to their lands. In particular, they would have some say in the construction of pipelines and other potentially environmentally devastating projects. They might also have some regulatory authority over oil and gas. The actions of the Trump administration’s Environmental Protection Agency demonstrate that they have no intention of respecting tribal input or the decision of the Supreme Court.

Those sympathetic to the EPA’s position argue that land is a finite resource. It’s unfortunate that we may sometimes have to break centuries-old promises, but the consequences justify doing so. State officials have obligations to their local economies. They can’t bring about economic growth and prosperity if nearly half of the state is off limits to any kind of expansive action. What’s more, Oklahoma is oil-rich; it produces 5% of the nation’s crude oil. This is a critical energy source, and these, too, are finite. As harsh as it may sound, some argue that access to important resources shouldn’t be denied because our great, great, great grandparents made promises. At the time at which they made those promises they weren’t fully informed about what they were bartering away. In response, one might argue that no one was “bartering” over anything. Native lands were stolen, and people were killed and displaced. Reservations aren’t a gift nor did they come about as a result of a free and fair trade.

Critics of the EPA’s actions argue further that economic growth need not be a society’s perpetual goal. Perhaps it’s time to finally focus on sustainability instead. The resources that Oklahoma seeks to exploit on tribal lands are resources that should be replaced with green alternatives anyway. Some writers have argued that the fact that our country is always barreling toward economic growth at least partially explains why indigenous knowledge regarding environmental practices is so often overlooked. For example, in Indigenous Knowledge and Technology, Creating Justice in the Twenty-First Century, Linda Robyn argues,

“The legacy of fifteenth-century European colonial domination placed Indigenous knowledge in the categories of primitive, simple, ‘not knowledge,’ or folklore. It comes as no surprise then that through the process of colonization Indigenous knowledge and perspectives have been ignored and denigrated by the vast majority of social, physical, biological and agricultural scientists, and governments using colonial powers to exploit Indigenous resources.”

Members of native tribes have critical insight to share regarding environmental issues. Not only do they know their lands well, they also have rich history, cultural customs, and practical wisdom regarding sustainable environmental practices. Colonizers and other opportunists have never cared much about this wisdom because sustainability was never the goal.

Nearly three hundred years after the Trail of Tears, little has changed when it comes to how some Americans view tribal lands. Growing cotton isn’t as profitable without all the free forced labor, but profiteers still lick their lips and look to tribal lands for other business ventures.