Halloween has just passed, and it is clear that public discourse on culturally sensitive and appropriate costumes continues to increase. These discussions about cultural appropriation are particularly prominent amongst America’s educated youth, who are on their way to becoming the next generation of leaders and advocates against racial discrimination. This heightened awareness is now slowly but surely making its way towards the world of sports.

Continue reading “The Sports “Race””

An Expectation of White Allies

Hello, White Allies.

I honestly do not expect every white person to know when they are offending me, but when I say that you are offensive, just accept and apologize. When you do not accept it, you are silencing my experience. My experience is important as it highlights the inequalities in America. It allows for other people from different backgrounds to interpret and understand that certain racial injustices do exist. As people began to understand these injustices, they are able to find proper ways to fight against them. This battle is bigger than any single person on this campus. My point in addressing Kappa Alpha Theta’s decision to wear Afros was not to shame them, but use them as an example of why the perpetuation of Black dehumanization still exists. The importance of highlighting this fact is to draw to all of your attention to the meaning of dehumanization: “the psychological process of demonizing the enemy, making them seem less than human and hence not worthy of humane treatment.” Perpetuating dehumanization normalizes issues such as police brutality, structural racism, and other injustices in America. If this continues to be normalized, then how do you expect our race to make progress?

I understand that some of the women apart of this fraternity may indeed fight for Black lives and claim themselves to be allies, but unfortunately, sometimes white allies make mistakes. You all do not know the complete history of Black culture. You are not able to identify things that you do not see on a daily basis. So, when I am telling you that Black Afros and White Afros are two different textures – just as curly is to coily; when I am telling you that the texture I witnessed on white women’s head at Greek God and Goddess dance was too close to Black texture, believe me. One would not know the difference unless one is Black and being oppressed for having this hair type every single day — so I forgive your ignorance.

A real ally would take full responsibility, apologize, and raise awareness that appropriation is real. White allies are important because they are the ones who hold privileges that I do not have. You all can easily sway the opinions of this university simply because you make up the majority. You all can easily change the laws that were created to oppress me because you have the same skin color as the group that is empower. But, in order to make changes and fight with me, you have to humble yourself. White allies must admit to being wrong when wrong, do some research, and stand behind Blacks. As you can witness from the rebuttal I received from my last article, Blacks’ experiences are easily silenced and swept under the rug. So, instead of saying things such as “I helped fight for you before,” say “I apologize” and support me as I decide what is best for me and my community. I should not have to challenge my white allies to make you understand that you are hurting me.

This Op-Ed is about current events at DePauw University. For more context, check out Ms. Jones’ Op-Ed from the previous week and the Op-Ed written in response.

What Happened at the Forum?

UPDATE: This article has been altered to include more eyewitness accounts.

The protesters of two weeks ago have sparked significant campus discussion. At the forum held in the late afternoon after the initial day of protests, many of the students in attendance expected to talk through the issues of the hate group that came to campus that day. These students were then confused when the forum went in a different direction. Some of the confusion may have arisen as a result of the fact that many students weren’t aware that there were two major events that took place on that day, not just one. A full picture of what happened on that first day of visits may help to explain why the forum took the direction it did.

What appears to be one issue (the protests led by Brother Jed and his group) is actually two. The first issue is the hateful message promoted by the visiting group that caused emotional distress for many on campus. However, there is an important second issue: the response by Greencastle and Indiana State police to some students of color who took part in the counter protest movement against Brother Jed’s group.

Brother Jed’s group, Campus Ministries USA, spoke prejudicially against many different groups. They called female students “whores” and said the following: “blacks are still slaves,” “blacks and gays worship a different God than us,” “it is not natural to put your penis in a rectum,” “carpet munchers keep your tongues to yourself,” and “militant feminists are ruining the world.” Their messages targeted almost every student on our campus, and every student has a right to be upset about them.

The second issue began after six women from Feminista! began a peaceful counter protest and were eventually joined by many other groups including: Omega Phi Beta, AAAS, Student Government, Lambda Sigma Upsilon, Sigma Lambda Gamma, etc. Individual protesters also came to show support.

The police, in an effort to protect students from lawsuits and jail time if they were to commit an act of violence against the protesters, eventually detained one black student. He was protesting peacefully and had not committed any such act of violence. Soon after, a white student threw hot coffee at the protesters. The student was taken away with a hand behind her back and escorted back to her dorm room.

Shortly after, a black student was angered by one of the protesters. When the student became visibly agitated, a group of staff stepped in to support him. One of the staff members involved, Yug Gill, stated, “[The student] had already begun to calm down and wanted to be left alone when the police officer entered the staff bubble around the student. [The student] did not resist the police officer.” The policeman slammed the student to the concrete followed shortly after by a staff member of color who was trying to de-escalate the situation. The police officers used their knees to pin them down and the student was placed in handcuffs. Neither of the detained men had committed a violent act.

The disparity between the police’s response to the detained men of color and their response to the white student who threw the coffee is a one clear factor in the outpouring of anger, grief and confusion at the evening forum. It is also clear how this issue is uniquely a racial one.

With this picture of the events it is reasonable to see how students present at the protest and who witnessed the detaining of their classmates and friends understood the forum to be on the subject of the unfair detaining of people of color by the police. It is also reasonable to see how students not present would have expected the forum to be regarding Brother Jed’s group and their hateful messages. Neither expectation of the forum was wrong.

What is wrong is accusing students who wanted to discuss racial disparities in policing that day of “hijacking” the forum and arguing that it wasn’t the time or place to discuss race issues. It is wrong to pretend that we only have space in our campus discussions for one issue at a time and to continuously prioritize whichever is more comfortable.

I hope that we can create a culture of listening at DePauw where we stop and listen when we are faced with something uncomfortable rather than shutting it down. I hope we can create an intentional community where we listen and trust each other’s experiences. Learning these skills is essential to healing divides that exist on campus.

Greisy Genao, Yug Gill, and Vivie Nguyen helped write this post and provided all firsthand account of the protest on 9/23/15.

A Collegiate Fear of Discomfort

College, particularly at a liberal arts institution, is a time for young adults to gain exposure to a wealth of new ideas and perspectives – typically, in order to become more open-minded and responsible members of society. A certain amount of discomfort is guaranteed to come with this notion. Having one’s beliefs and previous notions challenged can be difficult to process at times. However, today’s generation of college students are increasingly becoming less willing to participate in this discourse in the name of offensiveness and mental health. Additionally, on some campuses, “trigger warnings” have become a normal preface to any topic that could potentially be considered sensitive to someone, and the quantity of topics included in this range only continues to grow.

Continue reading “A Collegiate Fear of Discomfort”

Whiteness and Go Set a Watchman

This article has a set of discussion questions tailored for classroom use. Click here to download them. To see a full list of articles with discussion questions and other resources, visit our “Educational Resources” page.

The release of author Harper Lee’s long-awaited second novel, Go Set a Watchman, has sparked controversy even before hitting the shelves. Central among these controversies is the revelation that Watchman’s Atticus Finch, a celebrated character from Lee’s To Kill a Mockingbird, is portrayed as a harsh racist, more akin to the Ku Klux Klan than the defense against racism with which he is associated. As parents reevaluate naming their children after the character and others raise suspicions about the book’s publication, it is practically ensured that the text will be one of the most controversial publications this year. Yet, for others, the publication of Lee’s latest novel has provided the opportunity to air longstanding grievances that existed long before Go Set a Watchman – grievances that stand to change the way we think about To Kill a Mockingbird’s legacy.

Foremost among these criticisms are concerns about both novels’ depiction of racism, especially in light of characters like Atticus Finch. A recent op-ed written by Colin Dayan noted that To Kill a Mockingbird’s plot, traditionally praised as a stand against racism, contains more problematic elements in the way its black characters are presented. In Lee’s novel, Dayan argues, black people are either victims or are simply dragged “humbly in tow” behind white characters like Atticus. Characters like Tom Robinson, he argues, are primarily used to draw attention to the heroism of these white characters – to the point where many of the non-white characters are included “only to be helped or killed by whites.” Others, including acclaimed author Toni Morrison, have also drawn attention to the damaging “white savior” narratives upon which Mockingbird operates, presenting a reading of the work not often considered by white audiences.

While the dehumanized black characters in Mockingbird are certainly a problem, it may not be entirely the fault of the author. After all, Mockingbird is told largely from the perspective of a white child, a move Lee has said is grounded in her own experienced reality. The autobiographical nature of the book means that this white perspective certainly factors in prominently, which could be one reason the book exhibits the trends that Dayan describes. In some ways, then, establishing black characters like Tom Robinson as relatively dehumanized victims could have been central in building the worldview of a young white girl at the time, as Scout Finch is in the book. It could also be argued that the book may not have been as poignant if told from experiences and perspectives unfamiliar to the author. Personal writing is often incredibly powerful, and without its use in Mockingbird, the book may not have risen to prominence in the first place.

Regardless of author’s intent, however, Dayan’s points about the relatively dehumanized black characters still stands. In light of these points, it is necessary that we reconsider Mockingbird’s foundational role in educating about racism. For many students today, especially white students, reading To Kill a Mockingbird may act as a foundational early element of understanding racism. Within this educational process, characters like Atticus are too often held up as heroes, while texts focused on non-white characters fighting racism do not receive nearly the same focus. These trends are not isolated; in an op-ed for The Huffington Post, John Metta writes that discussions about racism in the United States are overwhelmingly considered through the feelings of white people – a trend certainly not helped by the “white savior” narratives like those in Mockingbird.

In this regard, countering the “white savior” narratives in Mockingbird necessitates that students be introduced to more varied representations. An excellent example would be Morrison’s books; works like Beloved and The Bluest Eye offer powerful anti-racist narratives from the experiences of non-white characters. Exposing students to these texts not only diversifies the experiences about which they are reading, but also helps counteract white-focused narratives that hinder discussions about racism. And while the legacy of Go Set a Watchman has not yet been cemented, it has become clear that white-centric accounts of racism like its predecessor can no longer act as the definitive source material on race.

Where Does the Confederate Battle Flag Belong Today?

Political pressure is mounting for the removal of the Confederate battle flag that flies on the state grounds of South Carolina in the wake of the Charleston Church shooting. In recent years, public debate over the flag that symbolizes racism to some and heritage to others has intensified. The divergent views towards the flag inflamed intense public dialogues about racism, culture and history ever since the mid-1950s. Under this circumstance in 1993, United States Senator from Illinois Carol Moseley-Braun claimed “it is a fundamental mistake to believe that one’s own perception of a flag’s meaning is the only legitimate meaning.”

As Moseley-Braun suggested, people should not impose one’s interpretation of the flag to others, and seeking to understand why people are offended by it and why people preserve it are actions that are necessary to take as educated citizens. In order to fully comprehend the implications that the flag gives to a diverse public, understanding the entire history of this symbol would become necessary as people from different backgrounds from a wide range of generations view the flag from a variety of perspectives.

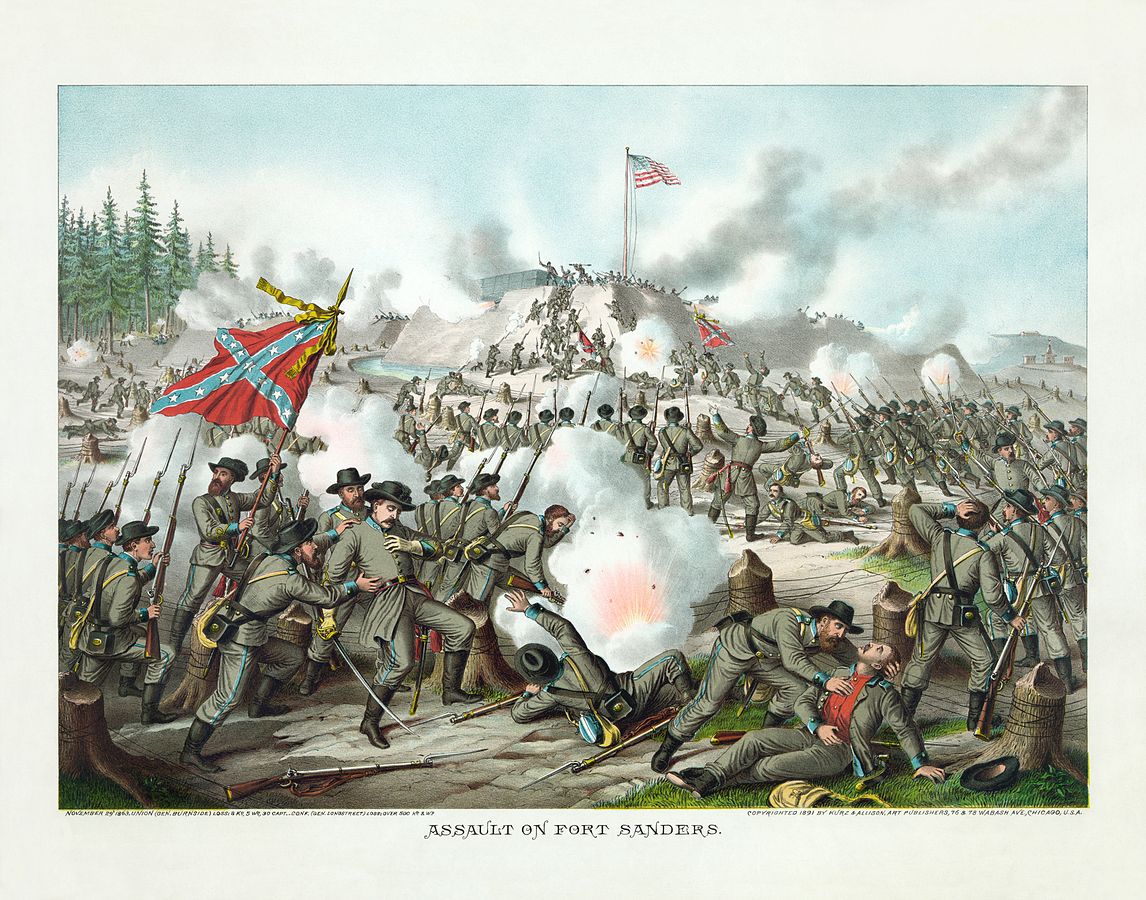

Unlike common belief, during the Civil War the Confederate battle flag did not explicitly symbolize racism nor slavery. Among the southern white population, less than 5% were slave owners, and thus, the majority of the Confederate soldiers did not own slave property. Racism prevailed both in the Union and the Confederacy as both parties did not give African Americans the right to vote and fundamental human rights. In fact, historian James McPherson argues that the main Confederate “cause” of the Civil War was to preserve their country and the legacy of the Founding Fathers, which derived from southern nationalism. As Lincoln recalled in his Second Inaugural Address in 1865, that slavery was “somehow the cause of the war,” the modern debate arguing that the Civil War about slavery, and therefore, the battle flag represents slavery is a mere simplification of history. The war was centralized on the issue on slavery, but one cannot naively generalize that all Confederate soldiers were committed to slavery and supported going to war for that cause.

The history of the flag does not end with the Civil War, but expands after World War II with the rise of the Civil Rights Movement. To many people’s surprise, the proliferation of the Confederate battle flag happened after 1954, when the U.S. Supreme Court declared that racial segregation in public schools was unconstitutional via the Brown v. Board of Education case. Although segregation was illegal, many southern states were reluctant to integrate schools. To show their resistance against integration, the Confederate battle flag came back in the public sphere.

The following year of the Brown case, George Wallace, governor of Alabama, raised the flag as part of his “Segregation Forever” campaign and endorsed it as a symbol of resistance. Not only political figures, but also segregationists brandished the flag to contest integration. It was at this time when the flag entered American popular culture as a symbol of opposition to integration, as Jonathan Daniels, editor of Raleigh News & Observer, lamented in 1965 that the flag had become “just confetti in careless hands.”

So, how should governments, corporations and individual citizens cope with a cultural icon that ignites intense debates? One must acknowledge the difference between public and private display of this flag. Public display of the flag (e.g. on the South Carolina state grounds) should be prohibited with the understanding that this flag symbolizes racism for a wide majority of the public. A governmental institution should not naively display a symbol of racism and show innocence in front of people who are offended by it. One must ask: “what would it be like for a Black citizen living in a state where a symbol of racism waves on the state ground?” Confederate flag images can harass or intimidate citizens and the government must not endorse such figure on its public ground. Moreover, the presence of the flag on the state ground excludes and ignores the population who do not honor it.

On the other hand, it is essential to distinguish between the flag as a memorial and the flag as a symbol of exclusion. The Civil War is undeniably a fundamental part of American history and culture, whose events still fascinate many Americans today. The history of the Confederacy is as valuable as the history of the Union, and no one can erase the four years that the two parties had fought. It is necessary to acknowledge that for many southerners, the Confederacy is part of their family history and the flag is a tool to honor their ancestors. Confederate heritage organizations have the right to privately use this symbol with the understanding that explicit use of the Confederate battle flag may offend others who are uncomfortable with it.

We live in a country where people come from different cultures, nationalities, and family backgrounds, and therefore, it is natural that there is a variety of perspectives on how one considers the Confederate battle flag. Many Confederate descendants look at the flag as a symbol of heritage, but this does not make the flag an honorable icon for everyone. A large number of people view the flag as a symbol of racism, but no one can assume that everyone who raises the flag is a racist. However, a governmental institution must consider the negative implications that this icon gives to the public. Even in private settings, no one can naively use this powerful symbol without considering the message that this flag might give to a wide public. In sum, seeking to understand the diverse meanings of the flag and engaging in honest dialogues would lead us to a better understanding of the proper place of the Confederate battle flag in modern day society.

References

Edward Pessen, “How Different from Each Other Were the Antebellum North and South?” American Historical Review 85 (1980): 1119-49.

James M. McPherson, For Cause and Comrades: Why Men Fought in the Civil War (New York: Oxford University Press, 1997).

John M. Coski, The Confederate Battle Flag: America’s Most Embattled Emblem (Cambridge, MA : Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, 2005).

The N-Word and the Politics of Obscenity

In wake of events like the Charleston Church shooting and Black Lives Matter protests, Americans have increasingly been forced to face the harsh racial realities plaguing the country. Such realities have demanded dialogue and conversation on a remarkable scale. And in encountering these dialogues, many have run into the same problem – deciding what language to use in approaching the topic.

Are You Your Avatar?

The online world has always been one of seemingly endless possibilities. In this space, it has been said, anything can happen and anything can be changed, including one’s own identity. And while this has been the case with many games, others have upended this model entirely. One of them, the online survival game Rust, is doing so to provoke debate about a topic rarely considered: race in the online world.

Black vs. White Space in McKinney, TX

The seemingly endless events of police brutality and the deaths of unarmed black people of the United States has captivated and divided our country. The most recent in the saga is the events of the infamous pool party of McKinney, Texas. Videos of the police officer under question, Officer Eric Casebolt show him arriving at a teenager’s pool party with mostly people of color in attendance and throwing a young bikini-clad fifteen-year-old to the ground, placing both knees and his full weight on her back, and shoving her face into the ground. He then threatens other kids who run to help her by pointing his gun at them. All attendees were unarmed and nonviolent.

There has been discussion over this incident, and much of it is argument over whether Officer Casebolt is racist or not. Those who defend Officer Casebolt argue that he had just responded to two suicide calls and was emotionally unstable at the time. But maybe this argument of whether the officer is racist or not is just a distraction from the real issue at hand, which is why did the police come in the first place? I believe the answer lies in the concept of white space vs. black space, who belongs and who does not, and how this tension leads to racial profiling in our country.

Before the officer arrived at the scene, the teens had been pestered by the security guard of the pool who continuously insinuated that they shouldn’t be there, though according to attendees, they had done nothing wrong. The security guard accused them of playing music too loudly and not having permission to use the pool. The security guard supposedly told them that their music had to be turned off, though attendees swear that the music was edited. Most teens in attendance lived in the community that owned the pool and thus had the right to its use.

Why would the security guard be uncomfortable with a large group of teens when there were groups of white teens at the pool as well? Why would their music be a problem if there were no curse words in it? Why would they assume that the teens didn’t belong, though most of them lived in the neighborhood?

On an episode called the “Birds and Bees” on NPR’s This American Life, one of the voices heard is Nikki Jones, who discusses how Americans racially code space. She says, “The ghetto itself is believed to be carried on the bodies of black people…that presents special dilemmas when black people are in white space. What is white space? Almost anywhere else. In these white spaces, black people have a special burden and they face a number of dilemmas. They have to prove that they belong there, the burden is on them to prove that they belong in a particular space.”

This rings true in the tale of the McKinney pool party. These teens should not have had to convince anyone that they belong in the neighborhood in which they live, let alone be subject to police violence while trying to prove their legitimacy. McKinney is not the ghetto, it is an average middle class suburb of Dallas, TX. By Nikki Jones’s logic, McKinney is white space, no matter how many people of color live there.

When examining events of police brutality against people of color, it is easy to get distracted by the violence. Though we need to discuss the violence and work to end it, our conversations must not end with “agree to disagree” moments of whether police violence was racist or not. Let us not forget to question why the police stopped these victims in the first place. Let’s examine if there was legitimate cause or if it was simply because they were a black face existing in a white space.

Whiteness, Accessibility and the Art Museum

It is easy to think of the art museum as a clinical space. Seemingly divorced from the outside world at times, these pristine spaces and the artworks that inhabit them often could not feel farther from real-life political struggles. Yet these sanitized, white gallery walls and climate-controlled rooms play host to a number of political debates that are intimately connected to the world beyond the museum gates.

Continue reading “Whiteness, Accessibility and the Art Museum”

Ferguson and Net Neutrality

The shooting of Michael Brown and the unrest in Ferguson raises a host of obvious ethical issues. One that isn’t so obvious is that it highlights the potential importance of knowing about net neutrality and algorithmic filtering. As Zeynup Terfecki has recently argued, what happened in Ferguson is a way to illustrate how net neutrality may be a human rights issue.

Let’s get clear about both terms first. “Net Neutrality” is the thesis that internet service providers should be neutral and enable access to all content and websites available on the internet. Furthermore, they should not favor, speed-up, block, or slow-down content and services from any website. Proponents of net neutrality hold that internet service providers should not be permitted to privilege content from websites and permit them to access a fast lane. Service providers also should not be allowed to intentionally slow down access to content from websites.

If you agree with those sentiments, then you are a fan of net neutrality. If, however, you think a company like Verizon should be able to reach an agreement with ESPN and let ESPN deliver streaming content more quickly to Verizon users, then you favor what I will call a “Tiered Internet.” I won’t go into the pros and cons of net neutrality here, but if you’re interested this Wikipedia entry has a nice summary of the arguments for and against net neutrality.

Now let’s talk about algorithmic filtering. Algorithmic filtering is simply a process by which computer programs instruct computers (via an algorithm) to scan a large amount of information and pull out the bits they are interested in. It has a ton of very useful applications, but we’re interested in how it can be used in the internet service industry. Algorithmic filtering is one of the things that differentiates Facebook from Twitter. Facebook carefully curates what shows up in your feed based on a secret algorithm that (in theory) will prioritize content that Facebook wants you to see. Twitter doesn’t do this. With Twitter you see an unfiltered stream of the tweets of everyone you follow in chronological order.

Terfecki noticed something odd about this difference. Her Twitter feed was loaded with tweets about Ferguson, but when she switched over to Facebook she saw nothing. Facebook’s filtering had managed to bury anything about Ferguson. No one is accusing Facebook of intentionally suppressing Ferguson posts, it’s just that for some reason Facebook’s algorithm prioritized things in such a way that Ferguson posts (for Terfecki) didn’t make the cut. Ferguson posts likely made the cut for many people. So the lesson is, algorithmic filtering has the potential to unintentionally hide important stuff from you that you care deeply about, as it did in Terfecki’s case.

However, there is another important lesson to be learned here, and this is Terfecki’s primary point. What Terfecki wants us to do is take a step back and think carefully about net neutrality. Why? Because tiered internet uses algorithmic filtering. If Verizon wants to prioritize ESPN content, it needs to write a program that automatically filters through everything streaming across its networks, flag content coming from ESPN, and route it to the fast lane.

Why should this have us concerned? Because the way in which service providers could filter and prioritize content are only limited by a programmer’s imagination. Internet Service Providers could, for example, get into the PR business. Are you planning on running for Governor? Do you want that embarrassing story about you from your time at college to go away? Service providers could charge a premium to speed up content from some sites that sing your praises and slow down content from sites that talk about your college days (assuming those sites haven’t outbid you), and voilà – the public is blissfully unaware of your past misdeeds.

The possibility of a truly informed citizenry would be further threatened if news media conglomerates got in the service provider game. News companies (with an agenda) could suppress stories from competing news organizations or media watch-dog websites and drastically shape the political message the country is getting. This is why we need to have a serious conversation about net neutrality. It’s not just about people who want to download large files without being throttled. It’s not just about delivering people free ESPN content quickly, if ESPN is willing to foot the bill. It is, as Terfecki notes, a human rights issue about ensuring that everyone has an opportunity to be a meaningful and well-informed participant in the political process.

Events like the Michael Brown shooting occurred all of the time in the pre-internet era, and the public was simply unaware of it. The internet changed that. Events that we should all be talking about are coming to light for everyone in the country at the same time almost the instant they happen, but we now have the technology to change that. We are rapidly approaching a future where the next Ferguson could happen, and a vast majority of us will be clueless.