In 2013, Simon Bramhall, a surgeon at the U.K.’s Queen Elizabeth Hospital Birmingham, performed a life-saving liver transplant on Patient A. Despite the surgery being a success, a few days later, the liver started failing. So, roughly a week after receiving their first liver, Patient A was back in the operating room for their second transplant, this time under the care of another surgeon. But, when this second surgeon opened up Patient A, they found something remarkable. Burned into the liver’s surface – the one that Simon Bramhall had implanted only a few days before – were two four-centimeter letters: “SB.”

Eventually, after some delay, equivocation, and the sharing of photos, it emerged that, yes, during the first operation, Bramhall had used an argon beam – used for cauterization – to sign the liver after he had transplanted it into Patient A. According to a nurse who had been present at the first surgery, when asked what he was doing, Bramhall said, “I do this.” He has since said he doesn’t recall saying this or that he must have been referencing something else if he did.

Bramhall’s rebuttal, however, is suspect. Not long after news of Bramhall’s actions emerged, a consultant anesthetist came forward and claimed that Bramhall signed his initials on another patient’s liver during a 2013 surgery, known as Patient B. Bramhall claims not to recall doing this.

Despite these revelations, Bramhall didn’t lose his job, at least not immediately. He left Queen Elizabeth Hospital Birmingham of his own accord, feeling that he was no longer welcome there, and continued to practice surgery at another institute until 2020; this is despite his 2017 admission of two counts of assault by beating concerning the liver brandings. Eventually, in 2022, the General Medical Council struck him off the medical register, arguing that his actions had undermined public trust in the medical profession.

Now, this case raises a whole host of questions, from the practical: Why did Bramhall feel the need to do this and has he done this to anyone else? to the ethical and legal: Why didn’t his colleagues immediately raise the alarm and why did it take so long for him to be charged and struck off once they did?

What I want to focus on here is not that he marked the liver unnecessarily but that he did so with a particular vision in mind. He didn’t do a squiggle, a circle, a smiley face, or something meaningless, but he used the argon beam to burn his initials into Patient A’s liver. Does this make a difference? Is it, in some sense, more harmful than if he had done another shape? Or some random letters?

First, it must be noted that the argon beam is commonly used during operation to stop bleeding, so its presence is not unusual. Also, the mark it makes is very shallow, with the beam only penetrating micrometers into the tissue. So, the amount of damage is limited. Finally, tissue can be used as a medium to test the beam’s effectiveness, meaning that the fact that the liver wasn’t pristine when Bramhall closed up Patient A isn’t an intrinsic concern.

This latter point is something which has been raised in Bramhall’s defense with Barbara Moss, a patient of Bramhall and now his co-author (they write thrillers together), arguing that:

He’s got to test the laser on the liver before he can use it – it’s a routine process. If I’m trying out a pen, I might as well just put my initial, because I can do that very quickly. The fact that he did it in a particular shape makes no difference.

This argument seems slightly odd given that, as another surgeon has noted, such tests normally consist of a couple of dots or a small wiggle, which happens before bleeding occurs, not after as, obviously, you’d test the laser before you have need of it. However, Moss’s argument got me thinking: does the shape matter?

One could make a case for the negative. Whether it’s someone’s initials, a circle, or a couple of dots, the damage done to the liver itself is minimal at most. Any mark is confined to the organ’s surface and doesn’t impact functioning. Indeed, if it hadn’t been for Patient A’s replacement liver failing, the liver may have never been seen again, and they would have never known about the mark’s existence. So, from a rather restrictive point of view, if one is concerned with the potential for physical harm that Bramhall’s actions might have caused, then it seems that it doesn’t matter what shape he etched into the organ as any shape would have the same impact – nothing at all.

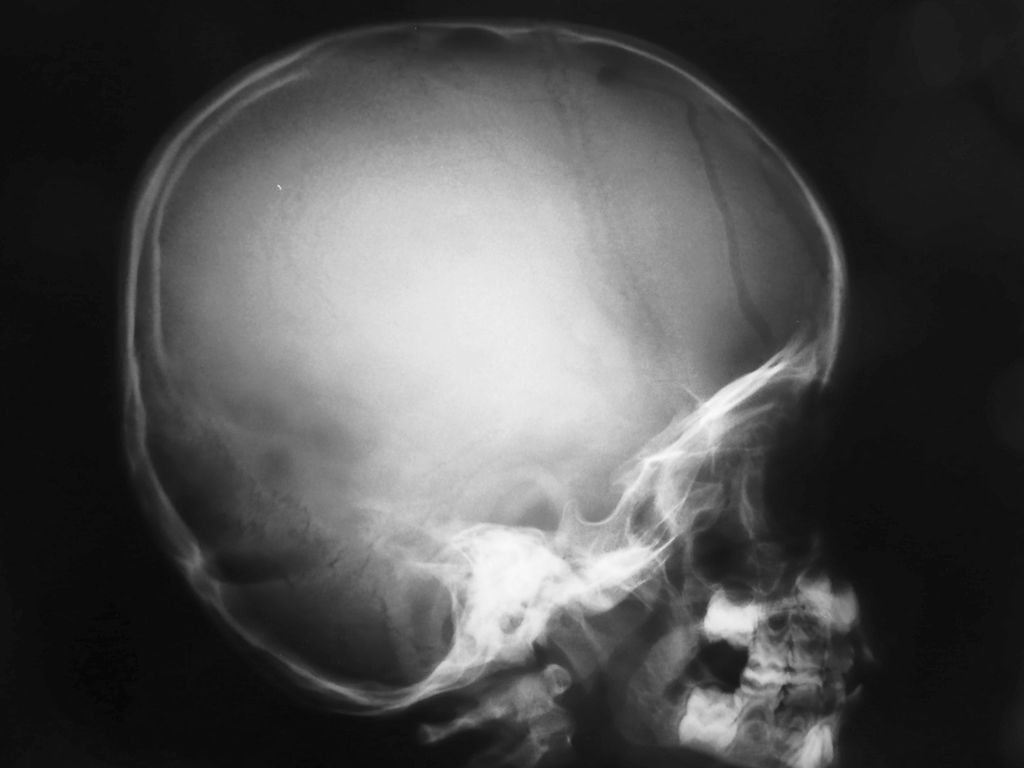

However, this would indeed be a very limited conceptualization of harm. It is now common for us to understand harm not only in a purely physical sense (getting hit with a hammer, being run over by a car) but also in a mental and cognitive sense (seeing someone get hit with a hammer, accidentally running someone over with a car). This understanding of harm emerged and became a central factor in Bramhall’s trial as, after seeing images of their branded organ, Patient A began experiencing symptoms of PTSD. This instigating factor led the Criminal Prosecution Service to charge Bramhall in the first place. It was not what he had done to the liver but what his actions had done to Patient A that mattered. So, with a broader understanding of harm, it can become easy to see how Bramhall’s actions might be considered uniquely wrong.

Yet, I am unconvinced that this gets to the nub of the issue. The idea of someone branding their initials into your internal organs is unquestionably horrifying, and I do not doubt that this could lead to PTSD, but I don’t think this fully captures the uniqueness of Bramhall’s offense. The fact that, above all other options, he chose to brand his initials into Patient A means there is something horrifyingly unique, even personable, in his actions.

To illustrate this, imagine that, to relieve the stress, two surgeons play a game of noughts and crosses (aka tic-tac-toe) on a patient’s liver, branding the game into the organ with an argon beam much like Bramhall did his initials. It’s not unreasonable to think that, upon finding out that their innards would forever carry the remnants of such a game, they would experience similar distress and symptoms as Patient A (for context, Bramhall says he knows someone who has done this very thing). The game’s presence would represent the reckless attitude such surgeons would have towards their patients and their jobs. Indeed, it would have to be someone holding an awfully cavalier attitude toward their profession to even consider such a thing. Yet, this lacks a certain degree at the core of the Bramhall case: the unabashed egotistical arrogance.

This is not to say that a surgeon who played a child’s game in the tissue of a patient’s organ wouldn’t have this critical flaw – I’m almost certain they would. Nevertheless, the imprinting of the game itself would be separate, to some degree, from the person playing it. It could have been anyone doing that. Bramhall’s initials, however, are an entirely different story. They are tied to him in a very personable way. And, yes, anyone could have put the letters SB into the patient, but someone with those initials did. If the liver hadn’t been rejected, Patient A would have spent the rest of their life walking around with a mark that intimately tied them to Bramhall; not an ambiguous game of noughts and crosses, but one of the very things that Bramhall uses to self-identify.

To emphasize this point further, imagine he branded his entire name into Patient A’s liver. The more personable and unique the mark signifying Bramhall’s actions, the worse it is (at least, that’s how it seems to me).

I suspect we will never really know why Bramhall did what he did (at least twice). He’s claimed that extreme stress led him to make the markings, but I find this doubtful. He has said that he thinks the backlash and subsequent punishment he’s received was over the top and that the GMC sought to make an example out of him. To use him as a way of warning other reckless medical professionals. This might be true. But, given the extreme power doctors hold over us – especially surgeons, who violate our bodies with our permission and are responsible for us when we are at our most vulnerable – might the example be worth making? Is it not better to make an example out of someone who did something terrible, than slap them on the wrists and potentially encourage such behavior in others?

It costs millions of pounds to train a surgeon of Bramhall’s caliber, and if nothing else, he was reportedly a technically sound surgeon. But if the cost of protecting the medical profession is his removal from it, the subsequent loss of his expertise, and all the time spent cultivating his skill, then it strikes me as a price worth paying.

I want to have faith that those who care for me will do just that, and this is fundamentally compromised if I must worry about those professionals using my flesh as an Etch A Sketch when I’m under the knife.