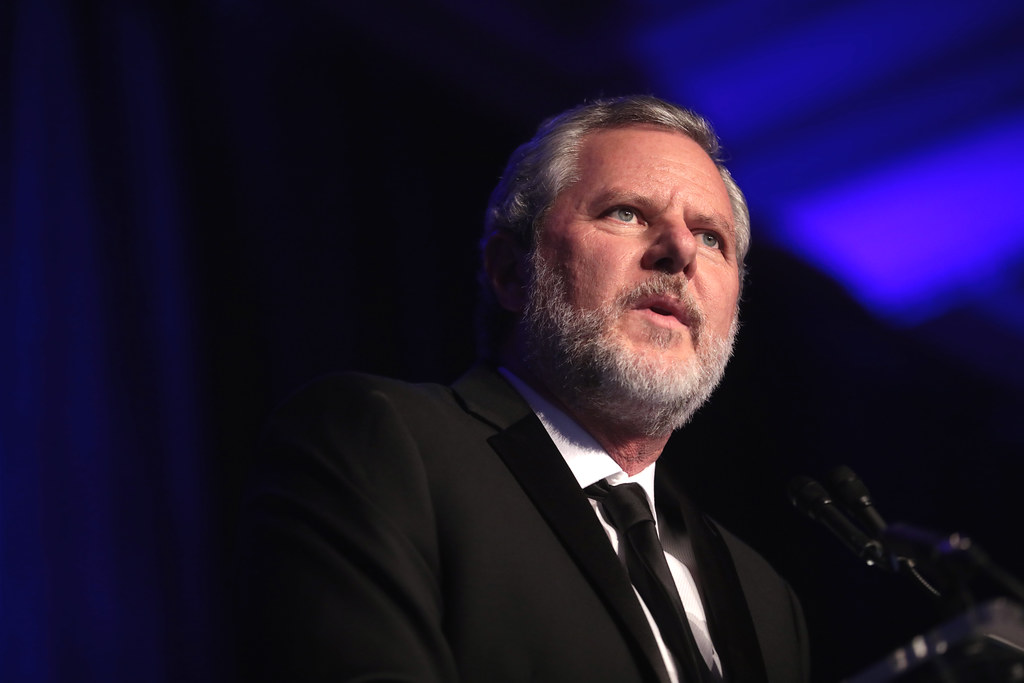

One of the biggest stories in the run-up to the U.S. election in November has been Trump’s choice of running-mate, JD Vance. The choice surprised many, given that Vance has previously been very upfront about his dislike for Trump, calling him “morally reprehensible” and even going so far as to refer to him as “America’s Hitler.” While some Trump supporters have held up Vance as an exemplar of a reasonable person who can change their minds, others have called him a hypocrite.

While it’s common to hear politicians exchanging barbs by accusing each other of lying, cheating, and other nefarious acts, hypocrisy is a charge that seems to cut particularly deep. But what’s wrong with hypocrisy, anyway?

Let’s first think about what it means to be a hypocrite. One intuitive characterization is that the hypocrite doesn’t “practice what they preach,” in one way or another – think about the vegan who chastises others for eating animals while ordering a hamburger, or the priest who sermonizes about the sanctity of marriage but is then caught cheating. Cases like these involve a kind of mismatch, one between the hypocrite’s actions and their beliefs, judgments, or other attitudes.

But now we have something of a puzzle: what’s so bad about one’s actions failing to align with their attitudes? We could, of course, judge the hypocrite based on the actions they perform: we might chastise the hypocritical priest for their infidelity, or the vegan for supporting an industry that harms animals. But the moral status of the actions the hypocrite performs doesn’t tell us what’s wrong with hypocrisy itself.

As philosopher R. Jay Wallace notes, the puzzle deepens when we recognize that some amount of hypocrisy is a common, even necessary part of our everyday lives. After all, we often act in ways that are not reflective of our attitudes in order to navigate social and professional situations: you might complain in private that someone is a bore but hang out with them anyway, for example, or tell a young family member that they should never drink alcohol before grabbing a beer once they’ve gone to bed. There are plenty of relatively harmless cases where we tell others to do as we say but not as we do. So why do some cases of hypocrisy seem so much worse than others?

One aspect that seems to be common throughout many cases of hypocrisy is deception. By acting in a way that doesn’t reflect their stated beliefs, the hypocrite seems to be misleading you in some way: after all, if they really believed something then they would act like it. So maybe what’s wrong with hypocrisy is that by being a hypocrite one is also a liar.

But this also doesn’t seem to be the whole story, since there are plausible cases of hypocrisy that don’t involve attempts at deception. Wallace considers a politician who unrepentantly criticizes behaviors of others that they themselves have performed: for example, a politician might have a platform that is centered on fighting corruption, but is open about their own history of shady business dealings; or perhaps they march in a protest among environmental activists despite their public involvement with oil companies. There is not necessarily any deception occurring in these cases: the hypocrite isn’t trying to fool you into thinking they haven’t done the things they’ve done, they’re just saying one thing and doing another.

We can also see how cases of genuine hypocrisy can sometimes be difficult to distinguish from cases of changing one’s mind. Of course, if someone has legitimately updated their beliefs, it seems unfair to call them a hypocrite when their actions don’t align with views they no longer hold. Indeed, in response to charges that his support of Trump constitutes hypocrisy, JD Vance has maintained that he has simply changed his mind.

Whether this is a satisfying explanation is up for debate. Some have argued that since Vance’s past comments were so extreme it is difficult to believe that he now genuinely supports a person he explicitly despised. But even if we grant that he has changed his mind, we might still feel that something is not quite right with Vance’s actions: if you’ve spent so long being so openly critical of someone, then joining their campaign and telling others that you should vote for them might still feel hypocritical.

The explanation as to why this might be the case can help us locate why hypocrisy seems to be such a significant moral failing: in failing to practice what they preach, the hypocrite holds others to a standard that they themselves do not adhere to. As Wallace argues, the mismatch between a hypocrite’s attitudes and their actions shows that they consider their interests to be more important than those of others, and that they ascribe themselves a moral standing they are not willing to extend to those they may be critical of. Hypocrisy, then, may seem so morally reprehensible because the hypocrite takes themselves to be exempt from certain rules that they expect others to adhere to.

Philosophers Jessica Isserow and Colin Klein argue along similar lines: in their view, the hypocrite has “undermined any claim they have to act as a moral authority” by virtue of the mismatch between their judgments and their actions. This is perhaps why the most egregious cases of hypocrisy seem to be those that come from people who take themselves to be in a position to cast moral judgments on others – the meat-eating vegan, for example, or cheating priest. Or vice-presidential candidate.

We can see why the charge of hypocrisy is levied with such opprobrium towards politicians: in virtue of being public figures in privileged positions, it is a serious indictment of character to fail to live up to the standards of moral authority that they are ascribed.

Whether Vance is a hypocrite is up for debate. Regardless, given how many times he’s reportedly changed his mind over social and political issues, the accusations aren’t likely to go away any time soon.