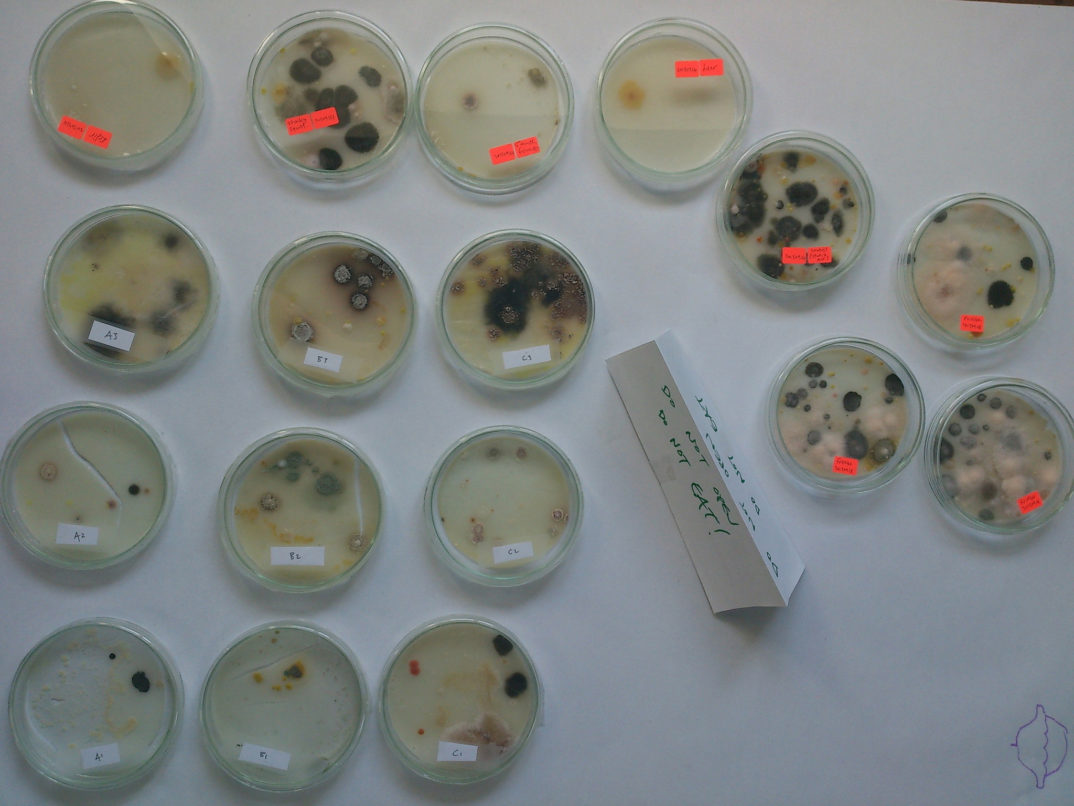

The problem of antibiotic resistance is real and growing. It is estimated that 700,000 people die from antibiotic resistant infections each year [1]. Further, every year, new multidrug resistant organisms emerge. We might soon face the global crisis of an era in which there is massive spread of bacterial diseases that cannot be treated by any currently available drug. In order to solve this problem, we must recognize that it has both scientific and ethical components: each time a physician prescribes an antibiotic she or he is required to balance individual patient needs with societal risks and benefits [2]. Further, even in the absence of antibiotic use, resistance is, and always has been, an evolutionary problem – natural reservoirs of antibiotic resistance exist even in pristine environments [3]. Added to this is the fact that over the last thirty or so years there has been a decrease in the number of antibiotics that have been developed and approved [4]. These factors make the problem of antibiotic resistance multifaceted and complex, but recent advances in basic scientific research show a promising way forward, even though previously implemented strategies to mitigate the problem have been largely unsuccessful. Continue reading “Solving Antibiotic Resistance with the Power of Evolution”

Do Terminally Ill Patients Have a “Right to Try” Experimental Drugs?

This article has a set of discussion questions tailored for classroom use. Click here to download them. To see a full list of articles with discussion questions and other resources, visit our “Educational Resources” page.

In his recent State of the Union speech, President Trump urged Congress to pass legislation to give Americans a “right to try” potentially life-saving experimental drugs. He said, “People who are terminally ill should not have to go from country to country to seek a cure — I want to give them a chance right here at home. It is time for the Congress to give these wonderful Americans the ‘right to try.’” Though only a brief line in a long speech, the ethical implications of the push to expand access to experimental drugs are worth much more attention.

First, let us be clear on what federal “right to try” legislation would entail. Generally, a new drug must go through several phases of clinical research trials before a pharmaceutical company can successfully apply for approval from the Food and Drug Administration to market the drug for use. Advocates of “right to try” legislation want some terminally ill patients to have access to drugs before they go through this rigorous and often protracted process. Recent legislation in California, for example, protects doctors and hospitals from legal action if they prescribe medicine that has passed phase I of clinical trials, but not yet phase II and phase III. Phase I trials test a drug for its safety on human subjects. Phase II tests drugs for effectiveness. Phase III tests drugs to see if they are better than any available alternative treatments.

Thus, “right to try” is a misnomer. First, these experimental drugs are still expected to meet some safety standards before patients can access them. Second, such legislation would not likely mandate that a pharmaceutical company provides access to their experimental drugs. The company can always deny the patient’s request. Third, these laws do not address cost issues. Insurance plans are unlikely to cover any portion of the costs, and pharmaceutical companies are likely to expect the patient to foot the entire bill.

Ethical debate over “right to try” legislation recapitulates a conflict that regularly occurs in American political debate: to what extent does government intervention to protect public welfare by ensuring that drugs are both safe and effective impede the rightful exercise of a patient’s autonomy to choose for herself what risks she is willing to take? Advocates of expanded “right to try” laws view regulatory obstacles set up by the FDA as patronizing hindrances. Lina Clark, the founder of the patient advocacy group HopeNowforALS, put it this way: “The patient community is saying: ‘We are smart, we’re informed, we feel it is our right to try some of these therapies, because we’re going to die anyway.’” While safety and efficacy regulations for new pharmaceuticals generally protect the public from an industry in which some bad actors may be otherwise motivated to push out untested and unsafe drugs on an uninformed populace, the regulations can also prevent some well-informed patients from taking reasonable risks to save their lives by preventing them from getting access to drugs that may be helpful. Therefore, it is reasonable to carve out certain exceptions from these regulations for terminally ill patients.

On the other hand, medical ethicists worry that terminally ill patients are uniquely vulnerable to the allure of “miracle cures.” Dr. R. Adams Dudley, director of UCSF’s Center for Healthcare Value, argues that “we know some people try to take advantage of our desperation when we’re ill.” Terminally ill patients may be vulnerable to exploitation of their desire to find hope in any possible avenue. Their intense desire to find a miracle cure may prevent them from rationally weighing the costs and benefits of trying an unproven drug. A terminal patient may place too much emphasis on the small possibility that an experimental drug will extend his or her life while ignoring greater possibilities that side effects from these drugs will worsen the quality of the life he or she has left. Unscrupulous pharmaceutical companies who see a market in providing terminally ill patients “miracle cures” may exploit this desire to circumvent the regular FDA process.

The Food and Drug Administration already has “compassionate use” regulations that allow patients with no other treatment options to gain access to experimental drugs that have not yet been approved. The pharmaceutical company still must agree to supply the experimental drug, and the FDA still must approve the patient’s application. According to a recent opinion piece in the San Francisco Chronicle, nearly 99 percent of these requests are granted already. “Right to try” legislation at the federal level would not likely mandate that pharmaceutical companies provide the treatment. Such legislation would likely only remove the FDA review step from the process described above.

Proponents of the current system at the FDA view it as a reasonable compromise between respect for patient autonomy and protections for the public welfare. Terminally ill patients have an avenue to apply for and obtain potentially life-saving drugs, but the FDA review process helps safeguard patients from being exploited due to their vulnerable status. The FDA serves as an outside party that can more dispassionately weigh the costs and benefits of pursuing an experimental treatment, thus providing that important step in the rational decision-making process that might otherwise be unduly influenced by the patient’s hope for a miracle cure.

What’s so Wrong with Doping in Sports?

When prestige, status, and money are on the line, it seems inevitable that someone will endeavor to skirt the rules to gain a competitive advantage. The payoff is too great for some to pass up. This is what we have seen time and again in international sports competitions with the use of illegal substances to enhance athletic performance. Doping is not something new and is unlikely to go away.

Drug Addiction: Criminal Behavior or Public Health Crisis?

It is painfully obvious that the United States is in the midst of an epidemic of opioid abuse. According to the US Department of Health and Human Services (DHHS), more people died from drug overdoses in 2014 than any other recorded year, and the majority of those overdose deaths involved opioids. DHHS and the Centers for Disease Control (CDC) claim that an increase in the prescription of pain medication is a primary driver of the opioid epidemic. According to the CDC, the amount of prescription opioids sold in the US has nearly quadrupled since 1999. However, Americans do not report higher levels of pain than they did in 1999.

Continue reading “Drug Addiction: Criminal Behavior or Public Health Crisis?”

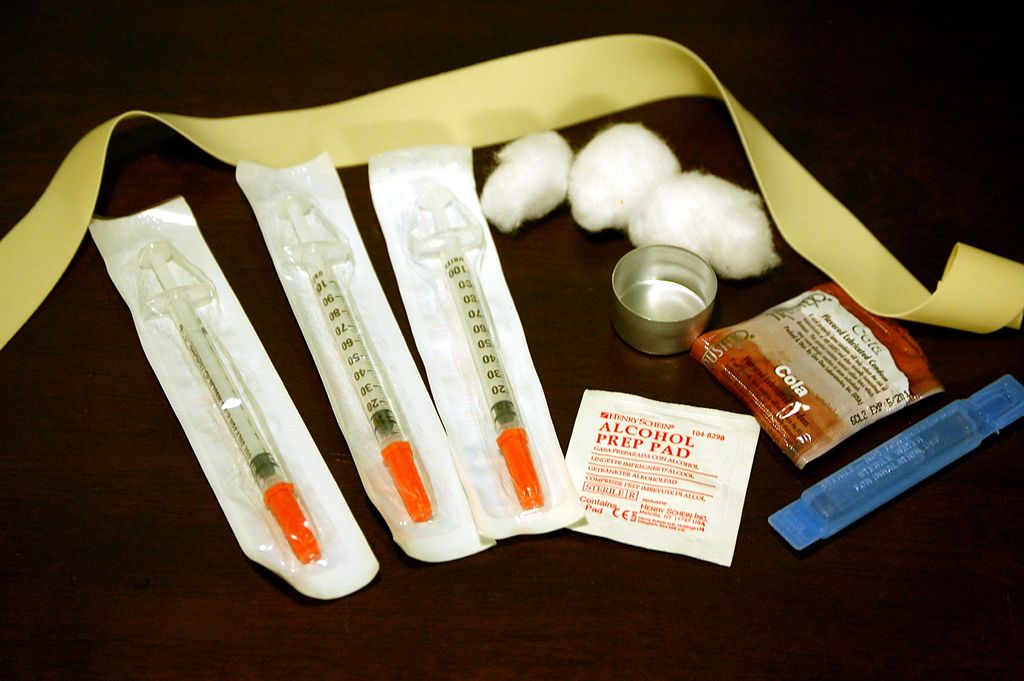

On Providing Safe Spaces for Drug Use

Under new legislation in Maryland, spaces will be provided for illegal narcotics to be ingested in clean facilities under the supervision of medical professionals. There are nearly 100 such facilities worldwide, largely in Europe, where they have existed since the early 1980s. In the United States, where rates of accidental death from opioid overdose have “quadrupled since the late 1990s,” these facilities are still largely a controversial possibility.

Anti-Psychotic Drug Use in Nursing Homes

A current, controversial area of medical, legal, and ethical concern in America is the distribution of anti-psychotic drugs to nursing home patients as a method of chemical restraint. According to the Code of Federal Regulations for Public Health, a nursing home “resident has the right to be free from any physical or chemical restraints imposed for purposes of discipline or convenience, and not required to treat the resident’s medical symptoms.” State laws reinforce the federal regulations and delve into further detail about defining and administering anti-psychotic drugs. An example from Indiana’s regulations includes requiring an “order for chemical restraints [to] specify the dosage and the interval of and reasons for the use of chemical restraint.”

Journalistic Ethics, Sean Penn, and Rolling Stone

Rolling Stone is in hot water over Sean Penn’s interview with notorious Mexican drug lord Joaquín Guzmán Loera, also known as “El Chapo.” The interview, conducted in October and published last Saturday, has raised concerns over Penn and Rolling Stone’s approach to the interview, and whether they handled the situation in an ethical manner. Numerous people have accused the magazine and Penn of violating journalistic ethics with the interview, while they have insisted they did nothing wrong.

Continue reading “Journalistic Ethics, Sean Penn, and Rolling Stone”

Drug Testing at Music Festivals

The prevalence of drug usage at many music festivals is not a secret, but how should we care for those who choose to take them? Recent drug-related deaths at music festivals around the world have sparked a call to action. But instead of banning drugs altogether, one Australian doctor suggests drug testing to promote safer usage among festival-goers. The process would involve festival attendees visiting an on-site laboratory to submit a sample of the drug they plan on taking. Workers would take 20-45 minutes to test the ingredients in the drugs and then pass along the information to the customer. Those who choose to take drugs will then know exactly what they are putting into their bodies. Similar testing techniques are already being implemented at select music festivals in parts of Europe and North America.

Marijuana’s Pesticide Problem

A wealth of information, both reputable and otherwise, can be found about the health effects of marijuana. Amid claims that the drug can cure cancer and studies documenting its negative health repercussions, it is sometimes difficult to get a sense of just how using marijuana could affect one’s health. However, one of the most clear-cut health concerns involving marijuana may not even stem from the drug itself. According to The Atlantic’s Brooke Borel, every time marijuana users light up, they are not just inhaling the intoxicating smoke. With it also comes sometimes-dangerous levels of pesticides – chemicals that, at least for now, go almost completely unregulated.

Communion of a Different Kind

When the authors of Indiana’s Religious Freedom Restoration Act (RFRA) passed it into law, marijuana churches were probably the last things on their mind. Yet, only a few months after the act’s passing, Indiana’s First Church of Cannabis has been established. Existing under the freedoms established by RFRA, the church operates on principles of “love, respect, equality and compassion,” with marijuana as its official sacrament. While many have cast it as a joke or a political statement against RFRA, the church also raises a number of questions about how the government can and should interact with organized religion.