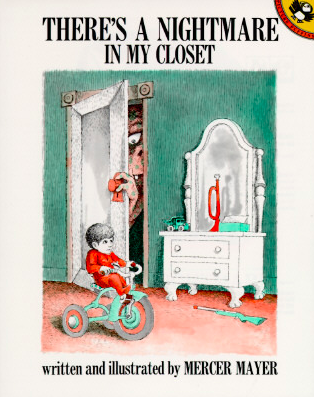

There’s a Nightmare in My Closet

Book Module Navigation

Summary

This story raises questions about reality, knowledge, ownership, identity, and control in a simple and accessible format for young children.

The young boy in this picture book knows that there is a big, scary nightmare living in his bedroom closet. He tightly closes his closet door to prevent the nightmare from visiting him in the night. One night, he gets tired of being afraid of the nightmare and decides to confront it.

Read aloud video by AHEV Library

Guidelines for Philosophical Discussion

Almost every child can provide an account of a nightmare they’ve experienced, and probably with many vivid details! However, Mercer Mayer’s familiar book does more than just offer a visual and written representation of one such account. For children of all ages, this book can question both the very nature of life and our human relationship to the things encountered throughout one’s own life.

There’s a Nightmare in My Closet raises deep philosophical issues of reality, knowledge, ownership, identity, and control in a simple and accessible format for young children. Tackling the oft-intimidating field of metaphysics, Mayer’s story asks us what kinds of things in the world are real. We, as readers, are invited to wonder whether or not objects in one’s mind, such as a nightmare, are real. Nightmares are an especially intriguing illustration because they are “seen” during the dream- or sleep-state when a person’s eyes are closed. Utilizing an experience common to young children, the first question set directs each child to survey the relationship between real things and our visual perception of those things. “Is an idea real? An emotion?” Asking these questions can lead to the collective effort of trying to understand what it inherently means for something to be real. Along the process, this topic also explores the essence, or basic nature, of thoughts and ideas. “What defines a thought? Is anything produced in a person’s head a thought? Is a thought a physical thing?” Curious folk have been proposing similar questions for years, and a brief look into the history of philosophy reveals that none yet has offered a convincing definitive answer. In fact, it is exactly this divergence of opinion in both popular and professional arenas, which makes the debate so interesting. Some people believe that ideas can be real things, immaterial in nature, but they get materially expressed through all kinds of human construction: written, spoken, or artistic mediums. Others have suggested that nothing is real unless it can be perceived by the senses. So although a particular book may communicate ideas to its reader, the ideas themselves would not exist without some copy of the book. Strict adherence to this belief would indicate that all real things have a measurable physical or material dimension; therefore, a thought or a nightmare would not be real. The first perspective has difficulty describing or even identifying the actual idea since it has no physical properties. However, the materialistic perspective cannot seem to account for the ways in which mere thoughts or emotions stimulate physical responses within the body and in the larger world. Children are not expected to solve these age-old disagreements; rather, it is intended that young minds can participate in a continuing dialogue that reveals the complexity of various issues. The philosophic tradition of debate welcomes the imagination of a child, and through stories, like There’s a Nightmare in My Closet, children can start refining the presentation and defense of one’s unique ideas.

In addition to metaphysics, this short story examines how human beings obtain knowledge. Officially called the study of epistemology, this part of philosophy is provoked by concerns that you may not be able to gain objective, true, knowledge about things, and that, in fact, such a truth might not even exist. More critical to this field of questioning is how you can ever be convinced of what we think we know. For example, when a child awakes panicked in the middle of the night, parents typically comfort their child’s distress by insisting that nightmares aren’t real; that “it was just a dream.” Now consider a question offered to audiences by recent popular movies, “What makes us certain that a dream isn’t real? What information would you need to be convinced that a dream was real? How can you be sure that our normal life isn’t a dream?” Perhaps nothing is real, and all the knowledge we think we possess about the earth is really just a deceptive illusion. French philosopher René Descartes believed that no matter how skeptical a person’s outlook, one can never doubt the existence of one’s self. If I try to doubt myself, it is me that must perform the intellectual act of doubting, and I prove that I exist. This argument is summarized by Descartes’ famous quote, “I think, therefore I am.” Further contemplation along this line challenges children to ask themselves what kinds of information they can truly know, if any at all, and how.

This style of engaged conversation regarding Mayer’s picture book also introduces simple ideas of ownership and control. Imagine the last time students in your classroom made art projects. Most likely, at least a few students refused to allow others to draw on their pictures or even touch their pieces of art. Their resistance implies a desire to control the objects they are creating and a sense that each person has a natural or given right of individual ownership, which extends to all their creations. Yet many moral and political theorists point to the infinite environmental or circumstantial factors contributing to a person’s choices; for example, time in history, geographical location, age of the person, peer pressure, available resources, etc. By establishing that various influences may have been inadvertently incorporated into one’s final creation, the last question set suggests that perhaps we have less control over our creations than we think we do. It also demands our consideration over who owns the object. “To what degree do we own the things we create? In proportion to the measure of control, we maintain over the object?” One of the greatest social benefits we gain from philosophy is its ability to contest commonly accepted beliefs. As a discipline, philosophy promotes active and constant evaluation of our personal beliefs and practices. This last question set shows not the literary or academic, but the real-world applications of such a learning and evaluation tool.

The primary goal of these questions is to generate a lively and productive discussion among any group of children, by use of a linguistically simple story. The secondary goal is to cultivate a love for doing the work of philosophy (which includes asking questions, stating observations, disagreements, and examples; and giving honest feedback – all of which are components of a child’s standard and frequent interactions with one another). This is an important activity because it teaches simple problem-solving skills while giving children the immediate opportunity to try out implementing those skills. Children must first identify the problem, then locate what is relevant and necessary to solve the problem, decide if the solutions are possible to obtain, attempt to reach a solution, and finally, evaluate the success of the solution and the process itself. Furthermore, all of this philosophical activity is placed within an environment of sharing and collaboration, to emphasize the effective power of different perspectives and different intellects working together in search of a common goal. Each question set attempts to highlight some topic or theme that children might find interesting and relevant to their own lives, both within and beyond academic schooling. Participants should be encouraged to draw upon their personal experiences in order to make and support claims about the world surrounding them. The discussion need not follow exactly the direction nor the content of the question sets. Instead, the natural curiosities of particular individuals and groups can be trusted to investigate a full range of philosophical subject matter.

Questions for Philosophical Discussion

Reality

This story tells about one little boy and his nightmare.

- Have you ever had a nightmare? What did your nightmare look like?

- What if you couldn’t see your nightmare. Would it still be there?

- Do you think you have to see something for it to be real?

- Can you think of things you’ve never seen, but that you believe are real (like maybe the continent Australia)?

- What about ideas or memories? What about your thoughts? Can you see them? Are they real?

- Can something be real to one person, but not real to another? How can that be?

- Try to remember a time when you told someone a true story, but they didn’t believe you. Was your story still true? Were the events still real?

- Is the little boy’s nightmare in the book a real nightmare?

- Was your nightmare real? How do you know?

- Imagine a situation where what seemed to be a dream was actually real. Is this situation possible?

- Can you ever be sure which is the dream and which is real?

Ownership and Control

In the story, the little boy calls the nightmare his.

- Did he create the nightmare?

- Do you think he can control the nightmare?

- Think about something you own, like a shirt, or a toy, or a lunch sandwich. What does it mean for something to belong to someone?

- What does it mean for something to be yours?

- What about your finger? Do you own your finger? Why or why not?

- Try to remember the last time you drew a picture in class. Did you want other people to draw on your picture? Why or why not?

- Can you think of things that might have affected how you drew your picture (for example: what colors you had, what assignment your teacher gave you, maybe whether you were happy or sad that day)?

- How much control did you have over the picture?

Original questions and guidelines for philosophical discussion by Rachel Bailey. Edited June 2020 by The Janet Prindle Institute for Ethics.

Find tips for leading a philosophical discussion on our Resources page.