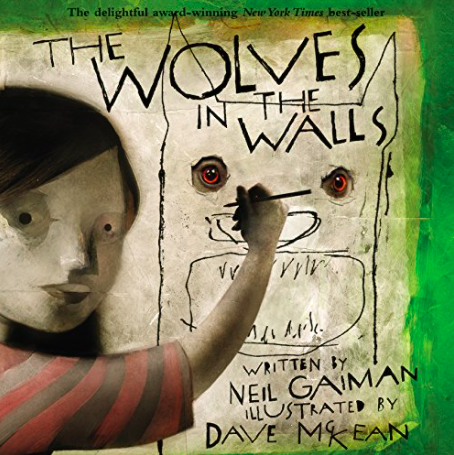

The Wolves in the Walls

Book Module Navigation

Summary

This story explores the conflict between belief and knowledge and considers how we come to accept certain ‘truths’ as reality.

Lucy believes that there are wolves living in the walls of her house, but her family doesn’t believe her! One day, the worst thing happens and the wolves come out of the walls. But as it turns out, the wolves coming out is not the worst thing ever.

Read aloud video by TTSJuniorTechnology

Guidelines for Philosophical Discussion

The Wolves in the Walls, by Neil Gaiman, brings to light numerous philosophical issues concerning knowledge, metaphysics, and ethics. When the main character, Lucy, hears wolves in the walls of her house, no one in her family believes her. Instead, they dismiss Lucy’s concern and remind her of the saying, “If the wolves come out of the walls, then it’s all over.” Lucy questions the meaning behind the saying, but no one in the family can give a clear and concise answer as to what it really means. It is here that the philosophical question of “what is knowledge” and the role of sayings, or “universal truths,” comes to light. As the story progresses, the dilemma of how we know what we know becomes more apparent.

The metaphysical question of what reality is also playing a big role in this book, as the reader begins to wonder whether what Lucy’s parents say is more believable than what her brother or Lucy says is true. Lucy believes that there are wolves in the walls, while her parents dismiss the noises as simply indicating the presence of mice or rats. When Lucy confronts her parents about the sounds, they scare her by repeating the saying, “If the wolves come out of the walls, then it’s all over.” This ethical issue is one that all children can connect with. Every child has experienced an adult threatening a child not to do something by reminding them of the bad things that will happen as a result. Many of the popular sayings can be viewed in this light, and it is important for children to begin questioning the validity of such statements simply because something is asserted as the truth does not make it any less of a belief. Through connecting the use of the saying, “If the wolves come out of the walls, then it’s all over” with how Lucy’s parents interacted with her concern about the wolves, a discussion about how we know what we claim to know and the manner in which we blindly accept them as unquestionable truths or facts can easily occur.

Through looking at how Lucy confronts her and her family’s fear within the story, children can begin to consider what things are worthy of fear and why. Is bravery identified solely as an act of fearlessness, or can a brave act arise from a moment of fear? Is a person brave only if others can identify the courage within her simple act, behavior, or appearance? The importance of confronting your fears arises when Lucy sneaks into the house to save her pig-puppet. A discussion about whether this was a brave or dangerous thing to do can lead children into thinking about the distinction between bravery and stupidity as well as the relationship between fear and bravery.

At the end of the book, Lucy begins to hear elephants in the walls. These last pages bring to light two very important philosophical issues in the areas of metaphysics and ethics. As Lucy questions whether or not to tell her family about the elephants, she talks to her pig-puppet. The pig-puppet responds, reassuring her that, “I’m sure that they’ll find out soon enough.” Throughout the story, Lucy treats her pig-puppet as if it were alive. Since Lucy believes that her pig-puppet really talks to her, does this make it true? This distinction between real things and imaginary ones thus arises, bringing with it the question, “What makes something real?” Does everything that is real also have to be alive, and is there a difference between being real and looking real? Additionally, do things need to have minds, be able to walk, talk, move, eat, and sleep to be alive? Here the nature of reality and what makes something alive presents itself, and it seems valid to ask whether Lucy’s closeness with her pig-puppet is any different than her friendship with other people. Children can easily relate to this issue, as they will be able to share stories of their special connection with stuffed animals or toys. It is important to get the children thinking about the nature of the imagination and what truly makes something real. It can also be beneficial for children to discuss when this distinction is necessary and when it is not.

When Lucy decides not to tell her parents about the elephants, an important ethical element arises. By not telling her parents, is Lucy, in a sense lying to them? The concept of lies really intrigues children, since they face making daily decisions based on what is “right” and “wrong” for themselves and others. The philosopher Kant believed that it was a person’s moral obligation and duty never to lie. In contrast, many other philosophers take the position that this obligation, to tell the truth, can be overridden in certain situations. For example, if someone’s life is endangered by a murder that is searching for a man, it seems valid for a person to lie to the murder about the location of the man being hunted. This action could be justified by means of the utilitarian principle concerning morality: that an action is considered “right” if and only if it promotes the greatest happiness. By using the book, the controversial topic of white lies, half-lies, and the withholding of important information can be discussed with children, as they can begin to analyze and weigh the outcomes of such actions.

The Wolves in the Walls combines an intriguing narrative with dramatic and original illustrations that will engage children of all ages. This story opens up the opportunity to easily initiate and engage students in philosophical discussions about bravery, reality, and morality. Throughout this book, the overarching philosophical issue is the conflict between belief and knowledge, and how we as human beings come to accept certain ‘truths’ as reality. A discussion of these questions will allow children to approach and view important philosophical issues in a different way.

Questions for Philosophical Discussion

Sayings

When Lucy’s mother reminds her of the saying, “If the wolves come out of the walls, then it’s all over,” Lucy questions what this means.

- Have adults ever told you a saying like Lucy’s parents told her? If so, can you give some examples?

- Do you always understand what a saying like, “a stitch in time saves nine” means or what it is trying to tell you?

- Where do you think sayings like this come from?

- Why do we have such sayings?

In the book, neither Lucy’s mother nor father can answer Lucy’s question of “what’s all over?” and “who says?”

- How can you say something that you really do not understand?

- Has this ever happened to you? Can you give some examples?

- Does the saying, “if the wolves come out of the wall, then it’s all over” help Lucy and her family?

- Can such sayings be wrong? If so, how can we tell when they are wrong?

- Has there ever been a situation where you said something you did not know was true or false?

Bravery

Lucy is the first to go back into the house and save her pig-puppet, while the rest of her family is too afraid of the wolves.

- Why don’t Lucy’s parents go into the house first?

- Do you think Lucy was brave in saving her pig-puppet?

- Would you have been able to do this?

- What makes Lucy brave?

- Does doing something dangerous necessarily make you brave?

Reality

In the book, Lucy talks to her pig-puppet like a friend, but the adults find this silly.

- Have you ever had a stuffed animal like Lucy’s that you also talked to?

- Do you think Lucy’s closeness to her pig-puppet is silly?

- Are there things you do that adults think are silly?

- Are adults always right about this?

- Why do you think Lucy talks to her pig-puppet?

- Is the pig-puppet alive?

- Does something have to be able to talk, move, eat, and sleep to be alive?

Morality

At the end of the book, Lucy begins to hear elephants in the walls.

- Lucy decides not to warn her family. Was this the right thing to do?

- What do you think would happen if Lucy had told her family that she heard elephants in the walls?

- Is Lucy lying when she doesn’t tell her family?

- Is it ever right to keep something from someone, and if so, how do you know when to tell them the truth?

- Have you ever known something to be true but not told someone? If so, why not?

- Is it ever okay to tell a “white lie” or to withhold information?

- What about the golden rule? Wouldn’t you always want to be told everything and to be told the truth?

Original questions and guidelines for philosophical discussion by Ariel Sykes. Edited June 2020 by The Janet Prindle Institute for Ethics.

Find tips for leading a philosophical discussion on our Resources page.