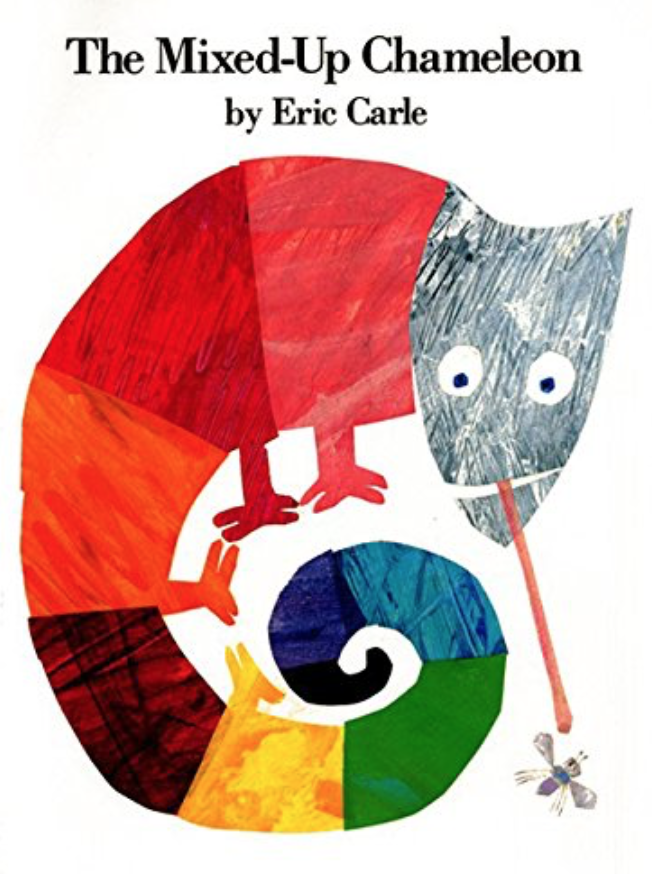

The Mixed-Up Chameleon

Book Module Navigation

Summary

The Mixed-Up Chameleon considers questions about happiness, change, and personal identity through a story of a chameleon at the zoo.

This is the story of a chameleon who is like any other chameleon. It changes color and sits around eating flies. One day, it goes to the zoo and is amazed by all the animals it sees. Whenever the chameleon wishes to change into a different animal, it does! It continues wishing until it ends up with fish fins, a giraffe’s neck, and a pair of flippers. Suddenly it sees a fly. The chameleon is hungry, but how can it eat the fly? It wishes it was a chameleon again and uses its super sticky tongue to eat the fly!

Read aloud video by Story Telling with Kim

Guidelines for Philosophical Discussion

The Mixed-up Chameleon touches on at least three different philosophical topics, namely, happiness, change, and personal identity, raising fascinating and delightfully puzzling problems.

Happiness

The story suggests that getting everything one asks for may not pave the way to happiness. In other words, what we think will make us happy might not do so after all. The Mixed-up Chameleon provides a great opportunity to discuss what happiness is, what makes us happy, and whether it is possible that fulfillment of one’s desires might not always lead to satisfaction. The first set of questions aims to bring out an interesting debate on the nature and pursuit of happiness, which goes back at least all the way to the Ancient Greece of Socrates, Plato, and Aristotle and is still very much part of philosophical debate today.

Change

All chameleons change and do so all the time. They change color mostly as a sort of language code, also for camouflage purposes, and in some cases as a means of regulating body temperature. When they change color, we may find it amazing to watch, but not particularly puzzling to think of. But the chameleon in the story changes differently. Bit by bit, page after page, it changes until there is no part of its original body left, and yet we still consider it to be the same individual throughout the transformation process. This poses some fascinating philosophical questions regarding change and identity over time.

Does it indeed remain the chameleon we meet on the first page throughout, or is there a point when one might say it is no longer the same chameleon or being? What is that “point,” and how do we determine it? Is it still our friend from the first page when it grows bigger and becomes white like the polar bear? When it grows a fox’s tail? When it sees the fly? This is, in fact, a formulation of a classical philosophical puzzle known as the Ship of Theseus, which asks when and whether a ship whose parts are replaced one by one would cease to be the same ship it was originally and become a different one. Another formulation of the same problem that might serve to illustrate this in a rather amusing way for children involves a favorite sock with a hole in it which is darned repeatedly over time until none of the original threads are left: is it still our favorite sock or is it a different one and if different, when might it have become a different one?

The puzzle is made all the more boggling if we compare our intuitions about a step-by-step replacement over time with a sudden, one-time replacement of parts. In a scenario where the planks of a ship are replaced over time with new planks, most of us would intuitively feel it is still the same ship. However, if we take all those planks and make a ship with them right now, we wouldn’t think it was the same ship. Why is that? What is the difference between the two situations? And if we are really in the mood, a further fun complication can be added to the problem. What if we had kept all the old planks of the ship and then decide to build a ship with them? Which would be the original ship, the one with the new planks or the one with the old planks?

Personal identity

Applied to human beings, the problem of change above is related to problems of personal identity, which are the subject of the last block of questions. The same question of identity over time can be applied to a person, adding further complexity to the matter. Are we the same person as we were when we were a baby? We look nothing like when we were babies, we have grown a lot, we have many new cells which have replaced many of our original cells. And yet we all say we are the same person as the chubby little baby in that photo. What does it actually mean to say we are the same person? How can we be so absolutely different and yet one and the same? What makes us that particular baby and not another baby in a different photo? Another question about personal identity raised by the book can be put like this: What makes you you? What do you need to keep to continue being you? Or, as philosophers also put it, what is your essence?

General Comments

Younger children may find it easier to engage in a debate on happiness than on personal identity. But not necessarily! It’s always a good idea to ask the child/ren first if they think there is anything particularly interesting about the story. It’s surprising how often children go directly to philosophically meaty issues if left to think about things freely.

Questions for Philosophical Discussion

Happiness

- The chameleon looks at what other animals have and wishes it was like them. Do you sometimes wish you had something other people have? Like what? Do you think it would make you happier to have those things? Why?

- The chameleon gets everything it wants. Does this bring it happiness? Why?

- Is it possible to get everything you want and not be happy? Is it possible that what makes us happy at a given time may actually make us more miserable in the long term?

- Say three things that make you very happy. What is it to be happy? And what is it to live a happy life? Could a happy life contain moments of unhappiness?

- At the end, the chameleon wishes to be itself again. What do you like about being yourself? Is there anything you don’t like about being yourself? Do you think liking things about being yourself gives you happiness?

- Have you ever positively not wanted something and, when given it, found out that it made you very happy?

- Do you think happiness is something we can set out to achieve or is it something that falls our way?

Change

- The chameleon changes a lot throughout the story. Would you say the chameleon is still a chameleon, and still the same chameleon, after becoming big and white like a polar bear? What about after growing flamingo wings and legs? After getting a fox tail?

- By the time it sees the fly, there is not one bit of the original chameleon’s body left. Is it still a chameleon? Is it still our friend from the first page? Why? Why not?

- If you gradually change all of something’s parts, can it still be the same thing? If we have a sock with a hole in it and mend it and then mend it again when it grows another hole, and again and again, until none of the original threads are left, but only the threads used for mending, is this the same sock we started off with? Why? Why not?

- If we change a ship’s planks over the years, until we end up with all new planks, is it still the same ship? Why? If we change all the planks of a ship at once, is it still the same ship? Why? What’s the difference between changing them gradually over time and suddenly, now?

- What if someone has kept all the old planks of the ship and decides to build a second ship with them? Which is the original ship?

Personal Identity

- What makes a chameleon a chameleon? What makes a person a person?

- If we took away your arm, would you still be yourself? How about both arms? Your body? Part of your brain?

- What makes you yourself? What would have to be taken away from you for you to no longer be yourself?

- What makes you the same person you were when you were a baby? How can we be so different (much, much bigger, with much more control over our bodies and much more complex thoughts) and yet the same?

Original questions and guidelines for philosophical discussion by Ellen Duthie. Edited June 2020 by The Janet Prindle Institute for Ethics.

Find tips for leading a philosophical discussion on our Resources page.