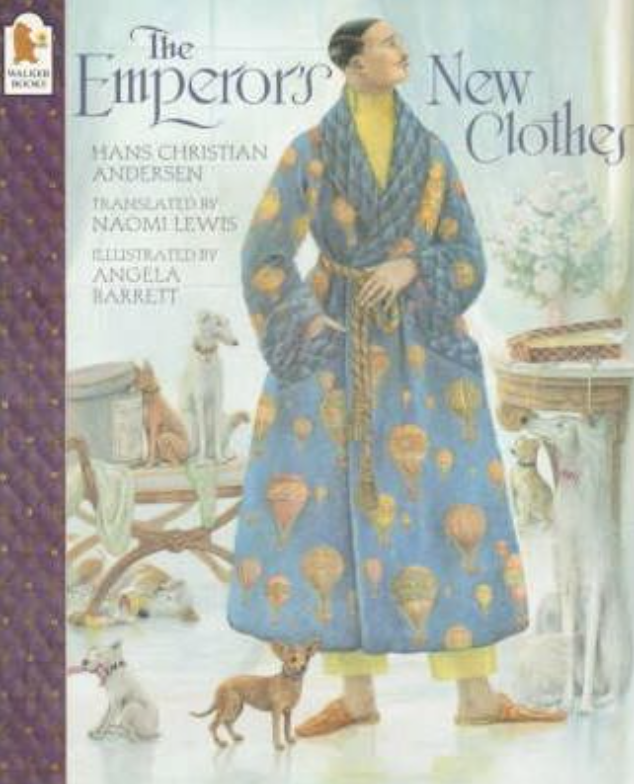

The Emperor’s New Clothes

Book Module Navigation

Summary

This classic tale raises question about self-deception, conformity, and obedience to authority.

An Emperor of a city is fond of clothes. Two imposter weavers enter his city and tell him they will create a suit for him that would be invisible to stupid people. The weavers only pretend to weave the suit and present the fake suit to everyone in the city. Everyone who looks upon the suit is troubled by what they cannot see, and whether they are inadequate or not. Everyone lies and says they can see the suit. A child breaks everyone’s delusion by shouting out, “the Emperor is not wearing anything at all!”

Guidelines for Philosophical Discussion

This story is a classic tale written by the Danish author Hans Christian Andersen, who wrote many famous children’s fairy tales in the 1800s that are still prominent today, such as The Little Mermaid, Thumbelina, and The Ugly Duckling. Like most stories of such age, this tale has multiple versions and translations, among various authors and story collections. Feel free to use any version that is available to you if you cannot acquire the one used in this module. All versions and translations typically follow the same basic plot, have the same basic elements, and present the same issues.

This story has great potential in being a prompt for philosophical discussion. When each character within the story is confronted with the invisible suit, they are also confronted with a complex moral dilemma. Should they tell the truth (not being able to see the suit) and accept their own supposed inadequacy, or lie and save themselves from social ridicule? This dilemma combines multiple philosophically interesting issues.

Self-deception

Self-deception is a process of denying or rationalizing away the relevance, significance, or importance of opposing evidence and logical arguments. This occurs very obviously in the story. The “rationalizing away” is seen when the characters convince themselves that they can see the suit. The “opposing evidence” is the fact that they cannot actually see the suit. This process of self-deception is used by virtually every character in the story in order to shelter themselves from the inconvenience of the truth. Reasons for their employment of self-deception are discussed further in the sections dealing with conformity and honesty. The “logical argument” that the characters are purposefully avoiding is presented at the end of the story by the young and innocent boy. The boy breaks the others out of their self-deception, with his proclamation that “the Emperor isn’t wearing anything at all!”

Honesty

Each character’s choice of whether to admit that they can’t see the suit or not is a good prompt for a discussion of honesty. Every character in the story, except for the young boy, chooses to lie rather than tell the truth about not being able to see the suit. The reasons they chose to be dishonest is a good topic for discussion. Kids can analyze the psychology behind the characters lying. A prominent reason is the social fear and anxiety that the suit dilemma presents: that is, if one cannot see the suit, one is stupid and doesn’t deserve a position in society. Reasons rooted in social status, conformity, judgment, trust, and individual morality can all bloom from discussion. After discussing the possible reasons for being dishonest, kids can be led into the deeper philosophical questions behind these reasons. Ask the kids why honesty is important or whether or not you have to be honest to be good. Asking when they have lied can relate their personal experiences to the situation of the individuals in the story, and help them empathize with how the characters in the story felt.

Another philosophical aspect of honesty that can be examined is what makes a lie. A lie is to state something untrue with the intention that people will accept the statement as truth. Is this immoral? The trickster weavers told the initial lie at the beginning of the story, announcing to everyone that they were making a magical suit when they were not weaving anything at all. Then they tell the supplementary lie that the suit will be invisible to stupid people. The other characters in the story believed these lies as the truth, causing them to lie themselves to support the weavers’ lies in order to save their own reputations. Were the characters who were tricked just as morally and ethically wrong in lying as the weavers? Were they bad guys too? This is an interesting discussion. It can be said that the weavers lied maliciously to seek personal gain and that the tricked characters lied out of fear and sought personal security. The question of when it is appropriate to lie can arise from discussion. Is it alright to lie to benefit yourself? What about in order to benefit the group or society at large? This can make for a great controversial discussion between kids. The discussion will reflect greatly on the kids’ opinions of morality and right versus wrong.

Conformity is the act of matching attitudes, beliefs, and behaviors to what individuals perceive as normal to their society or social group. This story does a good job of demonstrating the power of social pressures in influencing conformity. When each character confronts their inability to see the suit, they begin to fear for their reputation. Every character, including the Emperor, changes their perception to match that of the dominant group in order to fit in with that group. The dominant group is everyone who holds the false perception of being able to see the suit. Simply put, the characters changed their perspective to match that of the group’s, illustrating conformity. The desire to conform is also present in the real world. The Soloman Asch Experiments provide great insights behind the nature of conformity, and I encourage you to give them a look. One experiment can be seen here. In general, there are two types of social influence that can cause people to conform. Both can be spotted in the story. The first is called informational influence and the second is called normative influence.

Informational social influence occurs when one turns to the members of one’s group to obtain accurate information. Some characters in the story conformed simply because they believe in the group’s ability to determine what is true over their own perspective. Characters such as the Emperor’s ministers felt this influence because they supposed “if all my colleagues see the suit surely it must exist!”

Normative influence: Normative social influence occurs when one conforms in order to be liked or accepted by the group members. It usually results in public compliance, doing or saying something without believing in it. Practically every character in the story felt this pressure. They did not want to cause trouble within the group, so they chose to accept the suit’s public perception (even if they believed differently) so they would not be appear as an outsider. This influence was propelled even further in the story because of the added condition that not being able to see the suit made you inadequate in your peers’ eyes.

Questions for Philosophical Discussion

Personal Experience

- Have you ever convinced yourself that something was real/true(can use either) even if you knew it wasn’t?

- Have you ever done something just because everyone else was doing it?

- Have you ever believed something because other people you knew believed the same thing? [giving your own personal example may help clarify]

- Have you ever lied for a good reason?

- Do you always feel bad when you lie?

The Story

- Why did the characters in the story lie and say they could see the suit even though they could not?

- Why is reputation so important to the characters in the story?

- At the end of the story, the young boy tells the crowd the truth. Why did the young boy speak the truth when no one else did?

- Except for the young boy, all the characters in the story lied. Does this make them all bad? Why or why not?

- Do you have to believe something because everyone else believes it? Why or why not?

- Is honesty important?

- Can lying be good?

- How do you decide who you trust?

- What if the suit hadn’t been fake? How could one tell if it is real or not?

Original questions and guidelines for philosophical discussion by Mark Mudryk. Edited June 2020 by The Janet Prindle Institute for Ethics.

Find tips for leading a philosophical discussion on our Resources page.