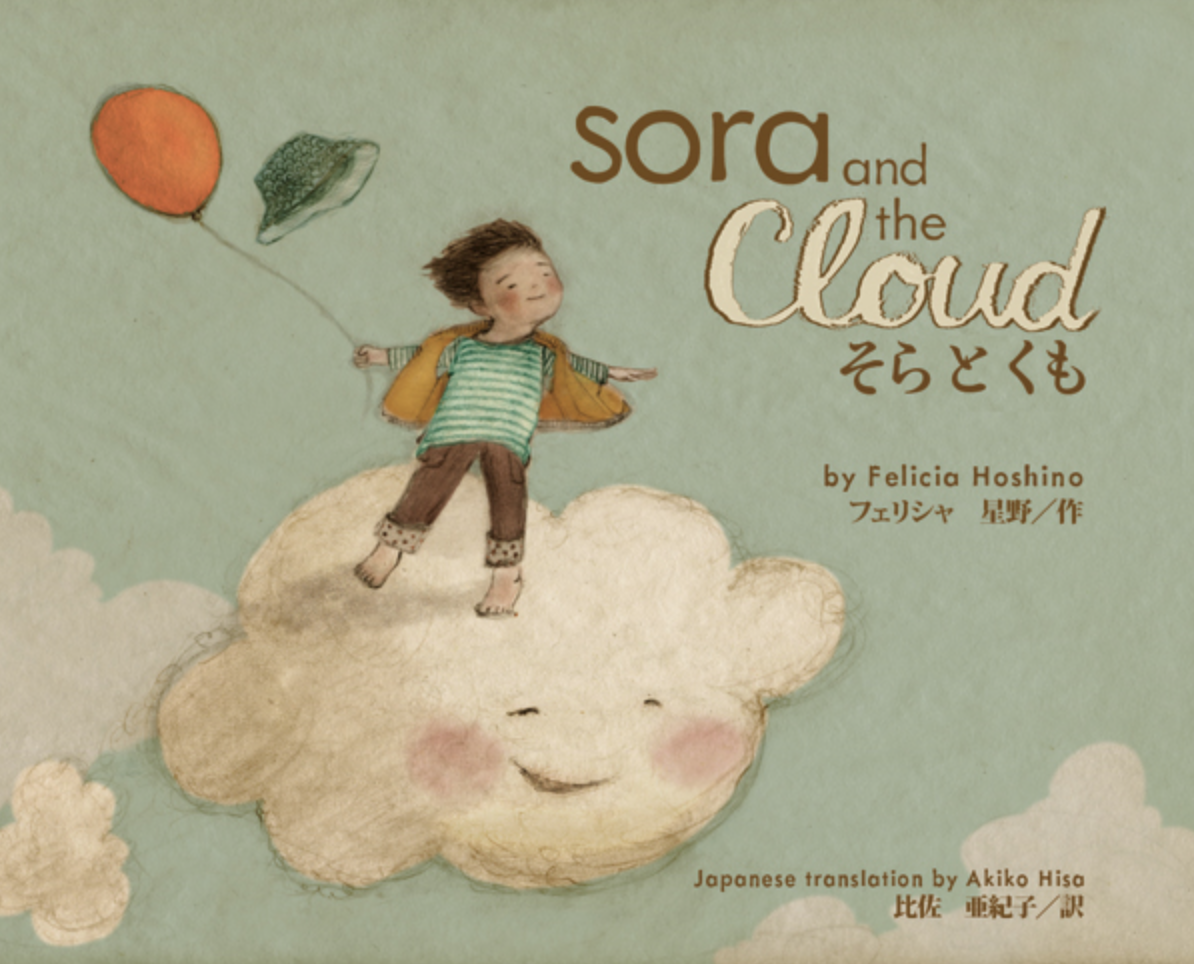

Sora and the Cloud

Book Module Navigation

Summary

Sora and the Cloud explores the nature of reality and the meaning of life.

Sora climbs over everything. One day he climbs over a really tall tree and finds a cloud at the top. Sora and the cloud then go on an adventure. They go to the amusement park, the festival of kites and many other fascinating places while they are up in the sky. They also dream together: Sora dreams of splashing in big puddles, digging in wet sand, and napping on a bed of grass. In the end, Sora says goodbye to his new friend and looks forward to his next adventure with the cloud.

Guidelines for Philosophical Discussion

Nature of Reality

By starting the discussion with a question directly related to the book, students will develop a solid foundation for the philosophical discussion to follow. Have the class list some of the activities that Sora took part in during his adventure with the cloud (i.e. flew close to a skyscraper, went to an amusement park). At the beginning of this discussion, it might be helpful to have the class come to a consensus that Sora was dreaming/daydreaming/using his imagination when he went on his adventure with the cloud. In other words, by assuming that Sora exists in a reality similar to ours (where flying on clouds isn’t physically possible), we assume that none of the things listed in the book actually happened. Depending on the age of the students, this will be helpful in the upcoming discussion of the nature of reality.

To differentiate between a couple of different definitions of “experience,” go back over the list of activities/experiences with the contextual framework of Sora having dreamt up these experiences (perhaps without using the word “experience,” instead you can use “feeling like you’ve been at the beach” vs. “being at the beach”). Have the students’ opinions changed on what Sora did or did not actually experience? What do they think it means to actually experience something? Likely, there will be a couple of different answers here: (1) physically being present for the activity/action, and (2) feeling the same emotions/consequences of the activity/action without being physically present (i.e. dreaming of being at the amusement park). You can draw out these answers by asking a question comparing an experience to a dream of that same experience. This is an important distinction to have as you transition into a discussion about the nature of reality.

Meaning of life and experience

After grasping the complexity of “experience” and different ways to “experience” something, students will be given a hypothetical scenario: if they could design their dreams and sleep for a really long time, would they choose to do so? This question is a simplified version of Robert Nozick’s “the experience machine.” To better contextualize this scenario, the teacher can also suggest different kinds of dreams/experiences students could design. These suggestions should aim to cover a broad range of human experiences in case students did not mention: to climb Mount Everest, to go on a vacation with family, to dive, to learn a new skill etc.

The teacher can then ask students who will choose to stay in their designed dreams, why they want to do so, and what kinds of experiences they want to design in the dream. The events students design in the dream will probably be related to happiness and pleasures in life. (If some students include unhappiness in their dreams, there is a discussion for that as well, which will be elaborated later.) The teacher could then ask the questions: Do you value these happy experiences in your dreams? Do you think happy and pleasant experiences are important for you, why or why not? Would they mean less to you if they only happen in dreams? Would you enjoy playing with your friends more if you guys are playing in reality, why or why not? These questions can let students think about why they value happiness/pleasures in life and whether such happiness/pleasures will be diminished or devalued in dreams. The teacher can also directly ask the question: if you can have completely identical experiences/sensations in the dream and reality, would you choose to stay in dreams or in reality? After a few answers and explanations, some students may find that realities and dreams are not that different if all pleasures in real life could be simulated in the dreams. Some students may think that there is something valuable about living in reality, for instance, you can have shared experience with your loved ones. At this point, students will have a better understanding of different things people value in life. Moreover, students are given the chance to investigate and re-examine the values of their experiences. For instance, some students may discover that compared to mere pleasures and fun they derive by spending time with family, they value more physically being with them and being able to share experiences with their families.

If no one mentions that they want to include sad, unhappy and unpleasant experiences in the dreams, the teacher could use this direction to ask students why they are unwilling to design unhappiness in their dreams. The teacher could also ask students to think about why someone may want to include painful experiences in the dreams. This discussion could be surrounding the overarching theme: whether we always need to/want to avoid pains and unhappiness in life. To stimulate the discussion, the teacher could ask students to think about the times when they at first felt sad and frustrated but later became happy instead. There are some examples: sincerely apologizing to one’s friends after a frustrating fight sometimes may make one feel happier and closer to one’s friends; finally solving a hard mathematical question after several disappointing attempts will give one greater satisfaction. These examples all show the experiences that were unpleasant at first but will become more pleasant and even more valuable in the future. The teacher could ask students whether there is something valuable in pains and failures and whether certain happiness could not be possible without pains and failures.

This discussion could also make a transition to a new topic about certain virtues in real life that may not be possible in dreams. The teacher can start the discussion with the question: Is it the same to climb Mount Everest in reality and your dream? There can also be a follow-up question: do you think you have done something more valuable if you climbed Mount Everest in reality instead of in your dream, why or why not? These questions could lead to the discussion of courage and bravery involved in climbing Mount Everest. The teacher can ask students whether they consider climbing Mount Everest in one’s dream to be courageous? The teacher can lead students to think about what they value in a courageous act: the possibility of death, to face one’s fear etc. The teacher can then ask students to think whether experiences in real life can show and reflect certain virtues of individuals and whether the same could happen in dreams; for instance, could someone be honest, selfless, and brave in dreams?

The Nature of Reality

To get to the bottom of their thoughts/judgments about the nature of reality, you can ask simple questions such as: Are your dreams real? If you dream about eating cotton candy, did you really taste it? The value judgments that follow from the answers to these questions have been addressed in the previous section. What you’re trying to get at here is more of a philosophical discussion about what constitutes reality. Is what happens in dreams real? What does it mean to say something isn’t real? Are both types of experience that the students have identified indicative of reality? Why or why not?

Questions for Philosophical Discussion

What is the nature of the reality?

- What did Sora do in the book? Start asking about specific things: Did he ride the cloud? Did he get up-close to a skyscraper? (Write this list somewhere visible for students.)

- Ask the students whether they think Sora was dreaming, daydreaming, using his imagination, etc.? Go back over this list and see if their answers have changed based on this inquiry. Why did they change? Or why not?

- What does it mean to experience something? (Through this question, you want to develop a couple of different definitions of “experience.”)

- Have you ever dreamed of things that actually happened in reality? Taking a test? Going to the amusement park? How can you tell that it is your dream but not reality?

- Could you taste, smell, touch, and see in your dreams?

- Do you have the same experience of going to the amusement park if you only dreamed of it? What do you miss by only going to the amusement park in your dream? (Especially if you believe your dream is real at the time.)

- Do you need to physically be at Mount Everest in order to say that you went to Mount Everest? Or physically be at an amusement park? Is there any difference in being present physically or being present in your dreams? If so, why?

- What’s the difference between dreams/reality if dreams could theoretically be the same as reality?

Does “getting in touch” with reality matter?/ Meaning of life

- What if you could design your dreams to do whatever you wanted and stay asleep for a long time? Would you do that, or would you rather stay awake and live your life? Why/why not?

- Would Sora experience something different if he was actually playing with sand by the beach instead of only dreaming about playing with sand?

- Is there something of value missing if he’s just dreaming?

- Why does he want to interact with the cloud again? What did he enjoy/value about the experience?

- Is there anything special and valuable in your life/ reality? Friends? Family? Would you get these same valuable things from dreaming about them?

- Could you feel happy just by spending good time with your family in dreams, why or why not?

- Could someone be brave/honest/happy in dreams?

- Could someone be considered brave if he/she saves someone’s life in a dream? / Could someone be considered honest if he/she admits his/her mistakes in a dream?

- Is there a virtue in an adventurous spirit? Or courage? Are these characteristics you can express in a dream?

- Could someone who climbs Mount Everest in a dream be considered brave? What are some important elements of bravery? Is the possibility of death crucial for someone to be brave?

- Could someone be talented and learn a skill in a dream? Could someone be considered an artist if he/she paints really well in a dream?

- Do you want to include pain and unhappiness in your dream, why or why not?

- Why do you think someone may want to include struggles and frustration in dreams?

- Could you think of your own experiences when initial frustration could lead to ultimate happiness?

- Could you think of examples when someone may be less happy if he/she does not endure pains and failures in the first place?

- Do you always want to/ need to avoid pains and unhappiness in life? Is there something valuable to unhappiness?

Original questions and guidelines for philosophical discussion by Sarah Kochanek and Anna Shao. Edited June 2020 by The Janet Prindle Institute for Ethics.

Find tips for leading a philosophical discussion on our Resources page.