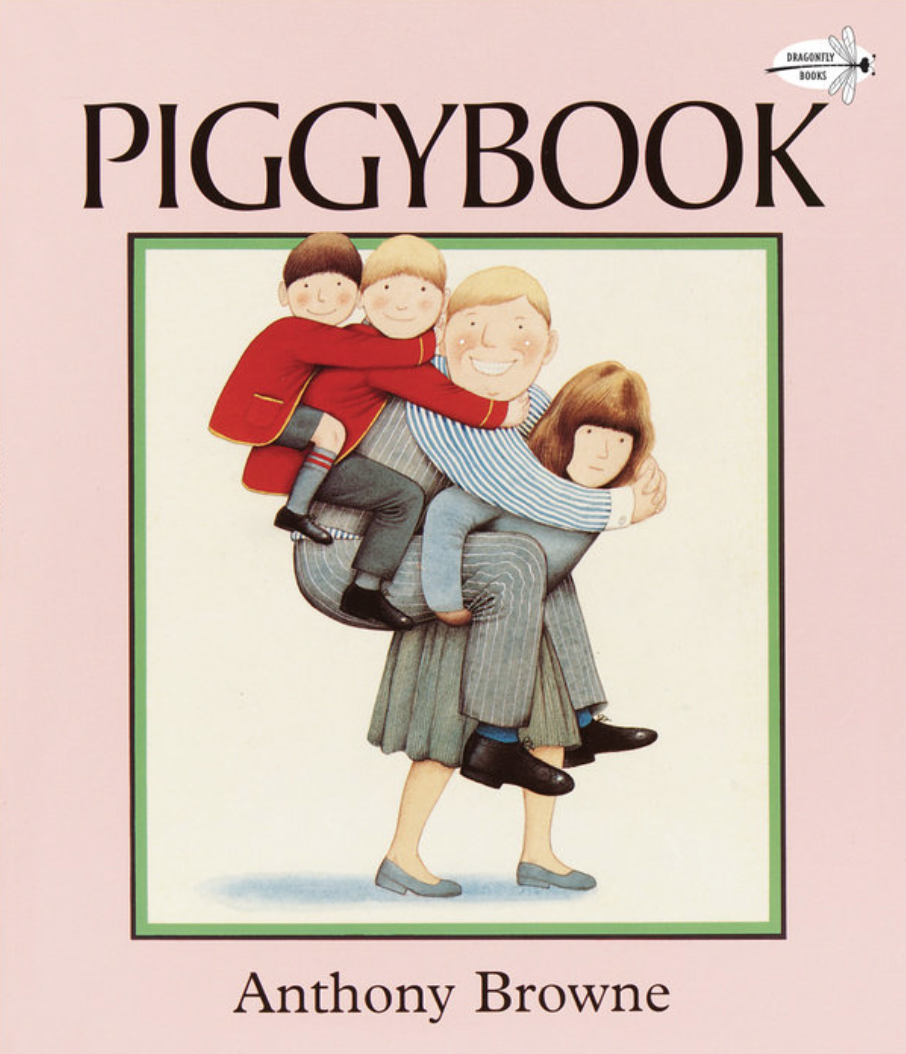

Piggybook

Book Module Navigation

Summary

Piggybook raises questions about gender norms, fairness, and autonomy through a story of the unfairly gendered distribution of household labor.

Mrs. Piggott cooks all the meals, washes all the dishes, makes all the beds, does all the ironing, and then goes to her own job. Meanwhile, Mr. Piggott and the two Piggott boys do nothing but wait around for Mrs. Piggott to feed them. One day, Mr. Piggott and the boys return home to find that Mrs. Piggott has left them. They struggle to cook and clean for themselves, and the house turns into a pigsty. When Mrs. Piggott finally returns, Mr. Piggott and the Piggott boys agree to help her with the cleaning and the cooking from now on.

Read aloud video by Reading Made Easy

Guidelines for Philosophical Discussion

Piggybook raises philosophical questions about gender norms, fairness, and autonomy. We live in a society that normalizes certain roles and attributes traditionally associated with men and traditionally associated with women, which is demonstrated in Piggybook. Piggybook also reflects the social reality of gender inequality within a family, specifically in terms of the distribution of labor.

To explore these issues with children, begin with questions about the structure of the family. Start with basic, factual questions: At the beginning of the book, how were the chores divided up? How was the family set up? To get children thinking about why Mrs. Piggott did all of the housework, follow-up with “why” questions: Why was Mrs. Piggott doing all the work? Why was the family set up the way it was? Some children may subscribe to gender essentialist ideas, or in other words, the idea that men and women each have distinct yet innate essences that are responsible for behavior and skill differences. Gender essentialism posits that men are naturally better at certain things, and women are naturally better at other things. If this is the case, challenge these students by asking for counterexamples. For example, if a student insists the reason men do not do laundry is that they are not good at it or because women are better at it, ask questions like: How do you know that women are better at laundry? Are all men bad at laundry? This invites other students to chime in with counterexamples. If no one mentions an example, feel free to bring up your own.

This is also an opportunity to ask the children about their own family structures and how their family divides up the work. Ask: Who does different chores in your family? In all likelihood, the children will bring up how they do chores as well. We believe this is an effective way to get the children thinking about the fairness of the way labor is distributed in the Piggybook family, as well as within their own families. This is also a good time to bring up fairness associated with equality in a relationship. Was the relationship between Mr. Piggott and Mrs. Piggott fair? Was it equal? Why or why not? You can also direct the conversation in a more general direction by asking questions like: What does a fair family look like? Does every family look different? Should people only do the work that they are best at?

If you are reading the book to older kids, it may be appropriate to bring up the philosophical concepts of adaptive preferences and autonomy. Adaptive preferences refer to preferences that someone in oppressed circumstances would not normally hold, but has come to hold because of the limitations of his or her situation. A common analogy for adaptive preferences is that of a fox that cannot reach higher, more delicious-looking grapes, and so convinces itself that it actually prefers the lower hanging, but less desirable grapes. Telling this story may be an effective way to get children thinking about adaptive preferences. Follow the story with questions like: Does the fox genuinely like the lower hanging grapes? Or: Why might the fox like the lower hanging grapes even though the higher hanging grapes are more delicious? In Piggybook, Mrs. Piggott makes it clear that she does not like to do all the housework for her family. However, hypothetically, what if she claimed that she did? Why would she be okay with doing all the housework? Is this a genuine preference? If Mrs. Piggott claims to be fine with her situation, is it still morally wrong or unfair? Is she making a bad choice?

Questions for Philosophical Discussion

Gender Norms in the Family

- How were the chores divided up?

- How was the family set up?

- Why was the family set up the way it was?

- Why is mom doing all the work?

- How do you know that women/men are better at ______?

- Are all men/women bad at ______?

- Who does different chores in your family?

- How does your family divide the work?

- Does every family look different?

Fairness in the Family

- Was it ok/fair that Mrs. Piggott did all the work?

- Was the relationship between Mr. Piggott and Mrs. Piggott fair? Was it equal? Why or why not?

- What does a fair family look like?

- Should people only do the work that they are best at?

Adaptive Preferences (for older children)

- Does the fox genuinely like the lower hanging grapes?

- Why might the fox like the lower hanging grapes even though the higher hanging grapes are more delicious?

- Hypothetically, what if Mrs. Piggott said that she liked doing all the housework? Why would she say this?

- Is this a genuine preference? How would you know?

- Is the situation still unfair?

Original questions and guidelines for philosophical discussion by Sarah Magid and Daniel Gorter. Edited June 2020 by The Janet Prindle Institute for Ethics.

Find tips for leading a philosophical discussion on our Resources page.