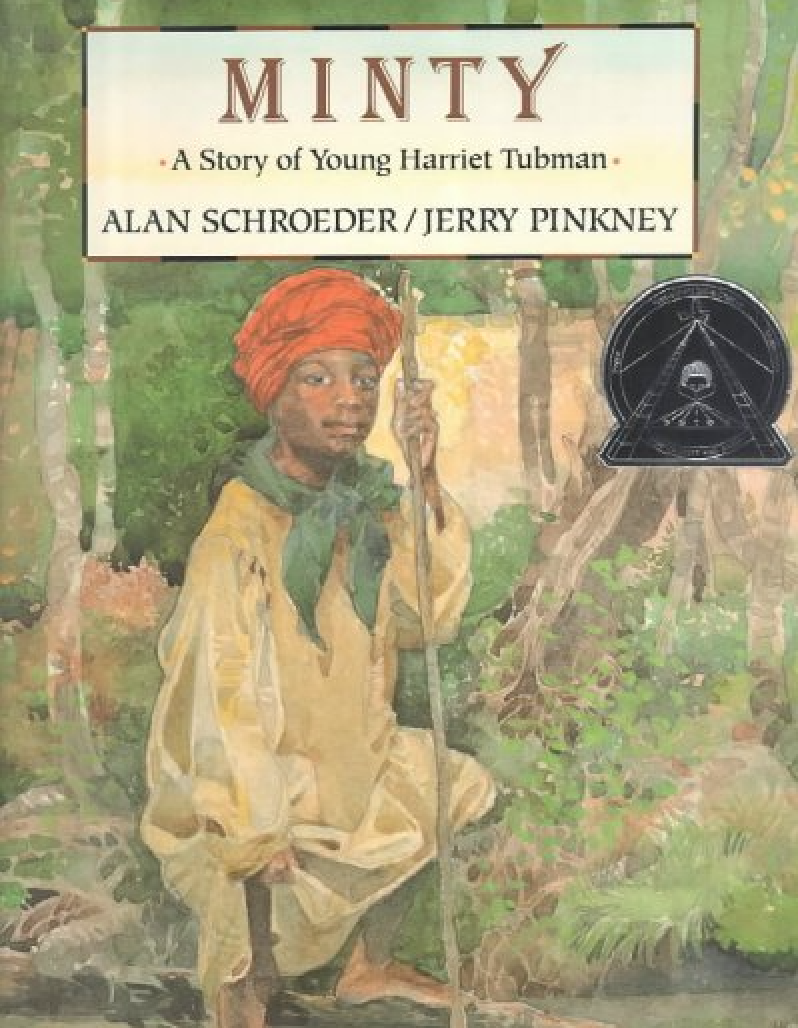

Minty

Book Module Navigation

Summary

This story about young Harriet Tubman will provoke a wide-ranging discussion with the topics of love and freedom featuring prominently.

Young Harriet Tubman was a slave in the 1820s on a plantation along Maryland’s Eastern Shore. In this story, Harriet – known as Minty as a child – is independent and feisty. Her father recognizes her spirited desire for freedom and teaches her survival skills that will be useful when she grows up to become the most famous conductor of the Underground Railroad.

Read aloud video (includes musical narration) by Woodmere Art Museum

Read aloud video (no music) by Sankofa Read Aloud

Guidelines for Philosophical Discussion

Minty, A Story of Young Harriet Tubman, is an account of Harriet Tubman’s childhood as a slave on the Brodas plantation on Maryland’s Eastern Shore. Although some of the scenes have been invented for narrative purposes, the basic facts are true. Author Alan Schroeder tells of Tubman’s early life in a way that reflects Tubman’s spirited desire for freedom and the obstacles she faced in its attainment.

Minty, as Harriet was known as a child, is independent and bright. Her dream of freedom burns brightly even when she is whipped for freeing muskrats from her master’s traps. The bold, brave 8-year-old is counseled by her mother to be more compliant and to try not to anger her owners any more than she had already done. Her father, however, recognizing her strong hunger for freedom, points to the stars in the sky, and teaches her survival skills that will be useful when she grows up to become the most famous conductor of the Underground Railroad.

Minty offers opportunities for philosophical discussion on the meaning of love, the difference between right and wrong, and the value of freedom. Minty’s relationship with her rag doll provides the first opportunity to get the children to discuss the meaning of love. The key here is to encourage the children to discuss the topic among themselves. The facilitator should try to avoid “teaching” the children, and instead encourage them to explore their own ideas and to work with each other to do so. Rather than delve into historical and predefined ideas of love, it is suggested that the idea of love be discussed with the children in a day-to-day context. What is meant by love? Are there different kinds of love? Do you love your friends in the same way you love your family? Can you love an object, and if so, does this idea align with the meaning of love that the children first decided upon? It is this very conflict that provides an opportunity for the children to learn to discuss, justify, and provide counterargument in conversation with one another. These are the types of ideas and opportunities that a facilitator will want to notice and encourage.

The philosophical classification of the nature of love spans a number of sub-disciplines, including epistemology, metaphysics, religion, human nature, politics, and ethics. Accordingly, explanations of love vary, and diverse categories have been established. Some argue, even, that love is irrational and cannot be explained. Love was described by ancient Greek civilization through the use of the words eros, philia, and agape. Eros refers to that part of love constituting a passionate, intense desire for something, while philia entails a fondness and appreciation of the other. Agape refers to the paternal love of God for man and of man for God but is extended to include a brotherly love for all humanity. Agape seeks a perfect kind of love that is at once a fondness, a transcending of the particular, and a passion without the necessity of reciprocity. One way to understand the question of why we love is as asking what the value of love is: what do we get out of it? One answer, which has its roots in Aristotle’s philosophies, is that having loving relationships promotes self-knowledge insofar as your beloved acts as a kind of mirror, reflecting your character back to you.

At one point in the story, Minty was shown how to collect trapped muskrats by the overseer. The conflict that arises when Minty lets the muskrats go provides an opportunity to encourage the children to discuss the idea of right and wrong. What do we mean by wrong? How do we decide if something is right or wrong? Where do the “rules” come from? Do the “rules” apply to everyone? Should there be a single set of “rules” for everyone? The second question set will help to guide this discussion.

Historically, the philosophical arguments regarding right and wrong highlight some of the difficulties in adhering to any one definition of right, and any one definition of wrong. First, one asks the justification of the definition of a right and a wrong. Historical argument naturally proceeds, then, into a discussion of the origin of the definition of the right or wrong to begin with and includes: a) from religious ideology, b) from an abstract world where concepts exist in some way, c) from agreement between people, d) from a consideration of duty, or virtue, and/or e) from a consideration of the consequences of various actions. In addition, over the course of history, the concept of right and wrong has sometimes been different for different groups of people. For instance, the same rules defining right and wrong did not always apply equally to free men and slaves, or to white men and Black. Nor do the same rules defining right and wrong apply, even today, to men and animals, or men and environments. Should there be a single system for all? Then again, why should there be?

That Minty wants to run away and attain her freedom is the main theme of the story. This provides the opportunity for the children to discuss the meaning of freedom. What is the difference between freedom and slavery? How do laws apply to freedom – are people under the rule of law still free? What is freedom of speech?

Freedom can be thought of as the absence of external constraints, or as simply, the opposite of slavery. In Minty’s case, slavery is the primary issue, but the story highlights the effect that slavery has on free will. Free will is taken to be the ability to exercise free will and make choices independently of any external determining force. Freedom is also sometimes thought within philosophy to signify the mastery of one’s inner life. Freedom, then, can be categorized into three areas – human rights, free will, and self-mastery.

Questions for Philosophical Discussion

Love

Minty loved her rag doll, Esther, very much, and hid her in the barn so that she could talk to her whenever she wanted.

- Where in the barn did Minty hide her doll?

- Could Esther, Minty’s doll, hear and understand Minty?

- Why did Minty love her doll so much?

- What is love?

- Are there different kinds of love?

- Do you love your friends in the same way that you love your family?

- Can you really love a doll?

- Does this agree with your original definition of love?

- Let’s summarize the things we have agreed on about love.

Right and Wrong

Mr. Sanders told Minty to put any trapped muskrats from the stream into the heavy sack he gave her.

- What did Minty do when she found muskrats in the traps?

- Why did Minty let the muskrats go?

- Was Minty right to let the muskrats go even though she was not supposed to?

- What makes something right?

- What makes something wrong?

- Does everyone have to follow the same rules for right and wrong?

- When is it right to do what you are not supposed to do?

- Let’s summarize the things we have agreed on about right and wrong.

Freedom

Minty’s father, Old Ben, took her into the forest and taught her many things, like how to catch fish with nothing but a piece of string and a nail and to swim in the still, muddy waters of the creek.

- Why did Minty’s father teach her these things?

- Why did Minty want to run away?

- Do you think Minty’s parents wanted to run away also?

- Why didn’t Minty’s parents just leave?

- Was it right for Minty to want to run away?

- What is a slave?

- What is the difference between a slave and a worker…like a housekeeper or a cook?

- Should everyone be free?

- What is freedom, then?

- We are expected to obey laws in this country. Does this mean we are not free?

- What is meant by freedom of speech?

- Does this agree with your definition of freedom from before?

- Let’s summarize the things we have agreed on about freedom.

Original questions and guidelines for philosophical discussion by Reisa Alexander. Edited June 2020 by The Janet Prindle Institute for Ethics.

Find tips for leading a philosophical discussion on our Resources page.