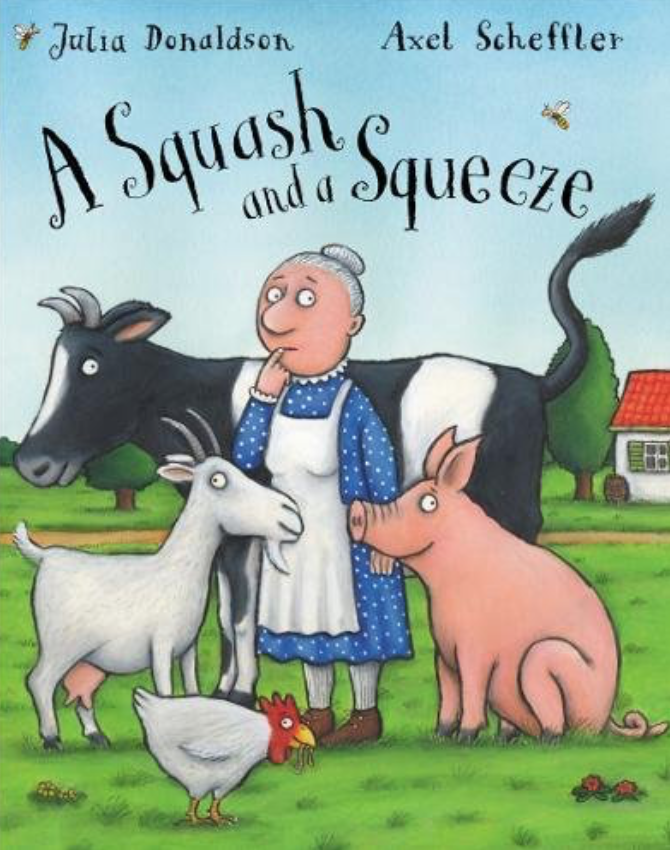

A Squash and a Squeeze

Book Module Navigation

Summary

A Squash and Squeeze examines what makes for well-being and how our desires are affected by our circumstances.

The story begins with an old woman complaining that her house is much too small. She enlists the help of a wise old man, who tells her first to take the hen in, then to take the pig in, and on and on until her home is full of animals with barely any room to move. She finally returns to the wise old man, and he tells her to let all of the animals out again. She does and is surprised at how spacious her house now feels – it is no longer too small.

Guidelines for Philosophical Discussion

This story brings up questions about what is necessary for a good life and whether a high level of well-being can be attained by changing one’s desires. If we assume that the woman fully understands that her house is the exact same size as before but is still happier at the end, then we can explore the various theories of well-being, and encourage students to think about whether achieving what they want is all that it takes to have a better life.

The first question set deals with the nature of well-being as it relates to the issue of adaptive preference. Well-being refers to what is ultimately good for a person or what makes them better off. Desire-fulfillment theories of well-being state that a person’s well-being is dependent on the extent to which their desires are fulfilled; anything that fulfills a person’s desires is good for them. This theory is complicated in cases of adaptive preference, where individuals’ preferences and desires may be deformed or lowered by their current circumstances (e.g. poverty). Philosophers such as Nussbaum have thus argued that the satisfaction of these deformed desires does not lead to an actual increase in a person’s well-being. In the case of the old woman in A Squash and a Squeeze, the first question set can be used to explore whether or not someone who has lowered their standards for desire–experienced adaptive preference–can really be considered to have a high level of well-being just because they have fulfilled their lowered standards. As students likely won’t be able to relate to or contextualize the concept of “well-being,” the idea of happiness may be used as a stand-in.

The first three questions push the students to consider what has changed in the story from the beginning to the end. Did the woman’s level of happiness change because of an actual change in her external environment, or a perceptual and mental shift? The next few questions ask students about whether changing her mind (or adapting her preferences) can still make the old woman happy, even if she is only happy because she has lowered her standards or ideas about what will bring her happiness. This encourages students to consider whether one can actually achieve a higher level of well-being by lowering or “deforming” one’s standards. If students are having difficulty imagining these scenarios, it may be useful to use more relevant examples: describe to students a scenario in which they really, really want a dog, but their parents won’t let them have one. Ask them if they decided that they didn’t want the dog anymore, would they truly be happy with not having it?

The second set of questions aims to allow students to ponder the plausibility of desire-fulfillment theories as well as objective list theories, which propose lists of items that constitute well-being and are not merely based on the fulfillment of an individual’s desires. Questions two through six get students to think about whether anything they desire is better for their well-being, and whether things that they desire may not make them have a better life. Questions seven and eight give students a chance to create their own objective list theories and to ponder whether these can be applied to all, that is, whether or not theories of well-being must be sensitive to the personal attitudes of each individual. Encourage them to think of broad themes that they need to be happy, rather than individual items which they want (as this would align more with desire-fulfillment theories). For question six, if students are having trouble coming up with ideas, you could give them examples of things that they do not want that are good for them, such as eating healthy foods.

Questions for Philosophical Discussion

The Nature of Well-Being and Adaptive Preference

At the end of the book, after she has let all of the animals out of her house, the old woman is full of “fiddle-dee-dees.”

- How big was the old lady’s house in the beginning? How big is the house in the end? Did the size of the house change in the end?

- Did the old lady think her house was big or small at the beginning?

- How does she think of her house at the end?

- Was the old lady happy at the end?

- Why do you think she is happier at the end of the book then? (If students are having trouble coming up with ideas, ask them the questions below.)

- Is it because she realizes her house is big enough, and she hadn’t realized it before?

- Or is it because she changed her mind about what she wanted (she no longer wants a bigger house)?

- If you really want something (like a dog) but you cannot get it, will this make you unhappy?

- If you decided to stop wanting the dog, would you then be happier because you now have what you want?

- If the old woman just changed her mind about what would make her happy, can we still say she is truly/actually happy now?

Note: In questions 6 through 8, the words ‘happy and unhappy’ are used for the students to measure their well-being, which might be easier for the younger students to think about.

Desire Theories vs. Objective List theories

Perhaps in the end the old lady does not want a bigger house anymore (she lowers what she wants) and becomes happier. Or perhaps the old lady didn’t change her mind about what she wanted, but rather she had had what she needed to be happy all along, but just didn’t realize it.

- Is there a difference between the things you need and the things you want?

- If you got everything you wanted, do you think you would have a good life?

- Are there things you want that aren’t good for you? For example: unhealthy foods?

- Do you think having these things is better for you, or worse for you?

- If you like to eat lots of candy and eating it makes you really happy, but at the same time you know this would destroy your teeth, would you choose to eat lots of candy and be happy? Or would you choose not eat it and potentially be unhappy yet healthy?

- Are there things that are good for you or will make your life better that you don’t want?

- What are the things you need to have to make you have a good life?

- Do you think those are the same for everyone?

Original questions and guidelines for philosophical discussion by Elizabeth Zhu and Abby Walker. Edited June 2020 by The Janet Prindle Institute for Ethics.

Find tips for leading a philosophical discussion on our Resources page.