Is Sport the Opium of the People?

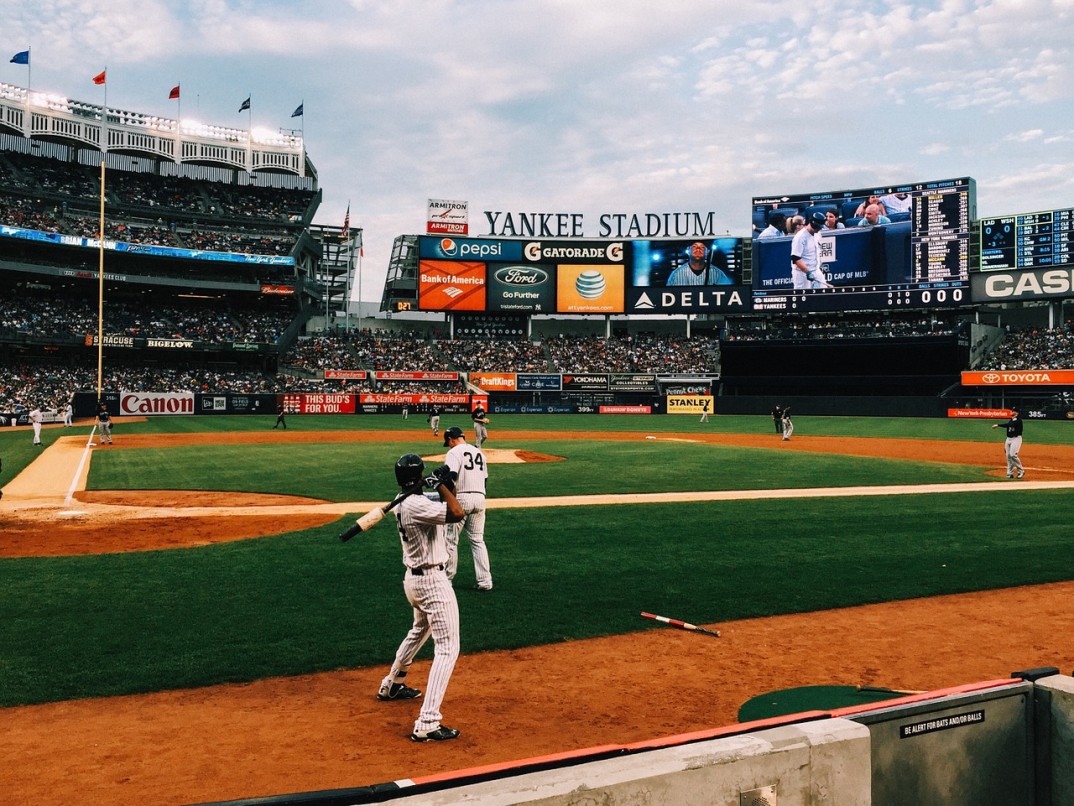

The Chicago Cubs have won the 2016 World Series. The curse is finished; after 118 years, the wait is finally over. Who the hell cares? Well, a lot of people. There has been an unusual hype regarding this sporting event. Five million fans showed up for the celebration parades.

For an ethicist, the natural questions to ask are: ” How many of those who know the details about the Curse of the Billy Goat, also know how the American voting system actually works? How many of those spending $1000 just to watch a game in a Chicago bar are willing to happily pay taxes or give to charity in order to improve local schools?

The answers to these questions, predictably, will be embarrassing. Sports culture seems deeply irrational. A long list of leftist intellectuals have made no secret of their disdain for the sports craze. Consider, for example, Noam Chomsky’s famous indictment of sports: “When I was in high school I asked myself at one point: ‘Why do I care if my high school’s team wins the football game? I don’t know anybody on the team, they have nothing to do with me… why am I here and applaud? It does not make any sense.’ But the point is, it does make sense: It’s a way of building up irrational attitudes of submission to authority and group cohesion behind leadership elements. In fact it’s training in irrational jingoism. That’s also a feature of competitive sports.”

Although the sports industry is mostly a 20th century phenomenon, Chomsky’s complaint is by no means new. The Romans already knew the alienating power of spectacles. Juvenal complained about how Roman politicians would use panem et circenses, bread and circuses, to keep the masses in check. As long as gladiators smashed each other in the arena, the common Roman people would forget about high taxes, conscription, and corruption in the ruling class.

Sport is very much a religion. For a lot of people, it is a passion that requires rituals and dedication, very much as Christianity or Islam would. But precisely, as Marx famously argued, religion is the opium of the people. It is a distraction from the real problems in life, and acts as a drug inasmuch as it numbs the masses and allows them to withstand oppression without rebelling. Sport is pretty much the same. Furthermore, very much as religion, sport can become fanatical, to the point of reinforcing dangerous nationalisms, as Chomsky reminds us in the above quote.

However, the Marxist view of religion, although helpful in many aspects, is still deficient. For, religion is much more than the opium of the people, and it can serve good purposes. Emile Durkheim (an agnostic himself) famously argued that religion increases solidarity through the common participation in the sacred, and it thus serves a very important social function. The same can be said of sports. Sure, as Chomsky claims, sport can lead to jingoism. But, there is a thin line between jingoism and healthy patriotism that may hold a country together under difficult circumstances. Rugby certainly played a significantly positive role as South Africa was getting rid of Apartheid, as Invictus beautifully reminds us.

Furthermore, sport is not the irrational activity Chomsky believes it to be. Norbert Elias famously approached sports from his “civilizing process” theoretical perspective. According to Elias, the fundamental characteristic of sport is to regulate behavior through the establishment of rules. By doing this, society keeps in check animalistic drives; i.e., it “civilizes” human beings.

So, yes, it is bad that someone may know Ben Zobrist’s batting average, but may have no clue about how many people died in the Holocaust or Hiroshima. But, by relating to other people that also know Zobrist’s batting average, that hypothetical fan may build communal links, overcoming differences in race, ethnicity or religion. By realizing that after three strikes the batter is out, the fan understands that, in life, there are also rules. And, by understanding that a runner on first may move to second with a sacrifice bunt, the fan may come to understand that there are times where he also has to make sacrifice for the good of the team; i.e., society.

Sure, there is an urgent need for a greater consideration of ethics in sports. Hooliganism, concussions, wife-beating, steroids, gambling against one’s team, corporate tax breaks, grotesque salaries, cultural appropriation, rogue nationalism, etc., are issues that need to be addressed. But, sport has a great potential for ethical development. Let us not throw the baby out with the bathwater.