Ethics of “Over-the-Counter” Birth Control

Birth control access has been a long debated issue in the United States. Obtaining birth control methods usually means women must go to a doctor’s office in order to obtain a prescription, which can be difficult, for financial reasons or if the hospital is religiously affiliated, for example. On January 1, Oregon’s “over-the-counter” birth control law went into effect, and .

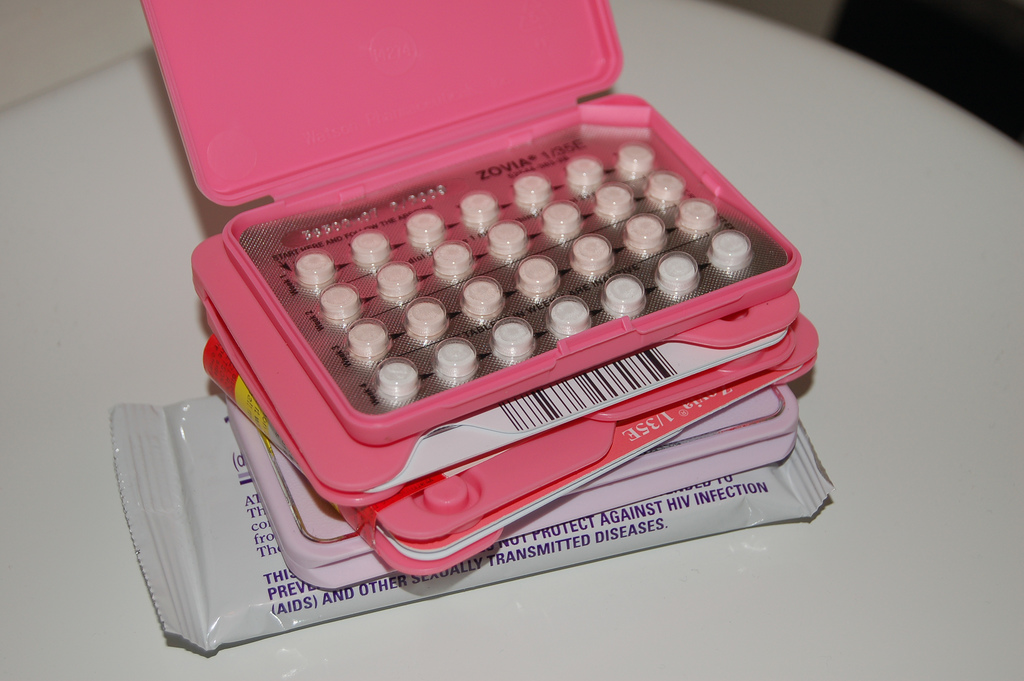

Many herald these new laws as beneficial to women’s reproductive rights. While “over-the-counter” is somewhat misleading – a prescription is still needed, but a pharmacist can provide it after a self-assessment completed by the customer at the counter – it still increases the amount of women who can access birth control. Under the Affordable Care Act, insurance must cover contraceptives. However, for uninsured women – many of whom may be at higher risk for unintended pregnancy – a doctor’s visit to obtain a prescription followed by paying for the birth control itself can cost over a thousand dollars a year. This has been cited as unethical, as it makes birth control something that only higher-income, insured women can afford to use. Women also have to spend 68% more money on out-of-pocket medical costs, partially due to birth control, than men do, which has also been called discriminatory and unethical. Studies show that birth control allows women to better take care of themselves and their family, and be in better economic situations, therefore restricting access to birth control is unethical as it denies women a chance at a better life. Additionally, the United States is actually one of the few countries in the world that requires a doctor’s visit for birth control; only 45 countries require a doctor’s prescription while 102 have it available at pharmacies. These laws are a move in the same direction as other international communities.

While many medical professionals believe that women, with assistance from a pharmacist, can determine whether prescribed birth control is right for them, others argue that the law is to women’s health and wellness. Pharmacists cannot screen for sexually transmitted diseases or cervical cancer, for example, and some believe that these laws will increase the risk to women, as they no longer have to come in for screenings. Oregon’s law contains an age restriction that requires underage women to receive a prescription from a doctor, while California’s law doesn’t; while it may encourage safer sex and reduce teen pregnancy, is it unethical to allow minors to obtain birth control without consultation from a doctor? While the medical community regards this a largely ethical and positive shift in policy, some are still concerned about possible negative implications down the road.