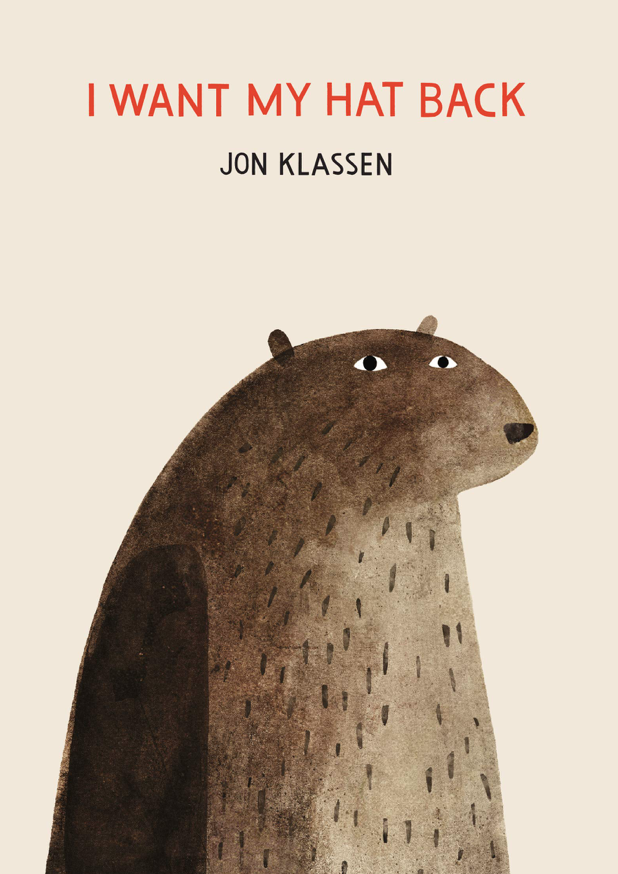

I Want My Hat Back

Book Module Navigation

Summary

When a bear loses his hat, he asks all the animals about it. One lies.

A bear has lost his hat and wants it back. He wanders around and asks all the animals he encounters whether they’ve seen it. As soon as the bear starts describing the hat, he remembers where it has seen the hat: on the head of a rabbit. The bear jumps up and runs back until he meets the thief and recovers the hat.

Read aloud video by Shon’s Stories

Guidelines for Philosophical Discussion

This book lends itself to discussion with its ambiguous nature. While the common reading of the text is that the Rabbit has stolen the Bear’s hat, and the Bear has eaten the Rabbit to take its hat back, none of these are stated outright. They are mentioned only in statements of denial, from which we may infer that they actually happen. Because these characters feel the need to deny actions even though no one has accused them of committing the actions, they paint themselves suspiciously. The ambiguity this creates frames hypothetical discussion nicely. We can easily ask questions like, “what if the Rabbit did not steal the hat?” and discuss what might change if this were the case. If the hat simply fell and the Rabbit found it, did the Rabbit do anything wrong by taking the hat? On the other hand, assuming the Rabbit stole the Bear’s hat, was it okay for the Rabbit to steal it? It should be noted that there is only ambiguity in the hat and the disappearance of the Rabbit. We know that the Rabbit lied about not having seen the hat, because it was wearing the hat when talking to the Bear. We also know that the Bear lied about not having seen the Rabbit, because they spoke to each other.

Most of the discussion for this story will stem from questioning the morality of certain actions, which are lying, stealing, and killing. Was it okay for each of them to lie? By asking this, we can establish with the students a baseline of moral rules: lying, stealing, and killing are wrong. Furthermore, we can discuss any differences between the Bear’s denial and the Rabbit’s. The structures of their lies is very similar, so is all that differs the subject of the lie? If so, is the difference in their choice to lie or what they chose to lie about?

After the Bear realizes he has seen his hat, he runs back to the Rabbit and yells, “YOU STOLE MY HAT!” This introduces a new conflict, the recovery of the hat. The book does not narrate how this happens, and not until the Bear encounters the squirrel do we get an idea. When the Squirrel asks if the Bear has seen a rabbit in a red hat, the Bear replies that he has not, and would never eat a rabbit. Beyond what we know to be a lie, that the Bear has not seen the Rabbit, we now have a possible answer to how the Bear recovered his hat. The Bear ate the Rabbit. Why else would it bring up the topic of eating rabbits? The squirrel did not ask if the Bear had eaten rabbits, just as earlier on the Bear had not asked the Rabbit if it had stolen the hat. Nevertheless, both the Rabbit and the Bear attest to not having done these things, which as we have discussed seems highly suspicious.

Both animals deny doing anything wrong, but the actions they deny differ. The Rabbit, if it did steal, did not do so in response to anything, while the Bear, if he did eat the Rabbit, did so in retaliation for the theft of the hat. In this way the killing of the Rabbit can be viewed as punishment. But is it just, or even proper, punishment? This discussion will cover ideas of reciprocity, such as what sorts of punishments fit different kinds of crimes, and will introduce students to the idea of how a punishment can be just. Then you might ask them to explain what makes something just. Later in the discussion, this will be brought up again in the form of reciprocity: whether or not justness comes from a punishment being equally as bad as the crime. By questioning alternatives the Bear could have taken, we bring into question the necessity of punishment. Perhaps death was not a good punishment for theft. Perhaps a less violent form of retribution could have been enacted.

From here, you could take the two actions of the Rabbit and the Bear and compare them, asking if their actions are equally bad, and then if thievery or murder is worse. The class may be divided on this, which is helpful, because it allows you to open a debate on how the animals’ punishments should differ. Since murder has been established as wrong, you can conclude that the bear ought to be punished. After establishing if the Bear’s action is worse than the Rabbit’s, you can ask how his punishment should differ or if it should? Perhaps you believe that the Rabbit does not deserve to die over theft, as death and lost property are not equally harmful, but you you might think that a punishment for killing someone could be death. In this way the Bear deserves the same punishment that the Rabbit received, even though in the Rabbit’s case, such a punishment was unjust.

This section can also touch on revenge, asking if it is different from punishment. This can introduce the idea of intentions coloring the morality of actions. Does murder differ from capital punishment? And what about how the intention of a crime affects how it is punished? If, for instance, the Rabbit only found the hat and was not aware that taking it would be thievery, does the need to punish the Rabbit change? This will also bring into play the idea of “two wrongs make a right.” Perhaps what makes the killing of the Rabbit unjust is not that it is too severe for the crime the Rabbit committed, but that it did not knowingly commit a crime.

To finish off this topic, you can ask if the idea of a punishment being just is dependent on the equality of the punishment and the crime. Is this a proper definition? Working with such a definition, can killing ever be a just punishment, especially if it is, as often viewed, the worst action one can do. Because if it is the worst of the worst, what could it justly punish other than itself?

Questions for Philosophical Discussion

Stealing

The Bear asks the rabbit whether it has seen his hat. The Rabbit answers, “No. Why are you asking me. I haven’t seen it. I haven’t seen any hats anywhere. I would not steal a hat. Don’t ask me any more questions.”

- Assuming the Rabbit stole the Bear’s hat, was it okay for the rabbit to steal the hat?

- Maybe the Rabbit did not steal the hat. If the hat simply fell and the Rabbit found it, did the Rabbit do anything wrong by taking the hat? Why or why not?

Lying

Both the Rabbit and the Bear lie in this story.

- Does the Rabbit’s response to the Bear (saying it has not seen a hat) make you question the truth of the response? Why or why not?

- Does the Bear’s response to the squirrel (saying he has not seen a rabbit) make you question the voracity of the response?

- Is there any difference between the Bear’s denial and the Rabbit’s?

Killing

A squirrel comes and asks whether the Bear has seen a Rabbit. The Bear answers, “No, Why are you asking me. I haven’t seen him. I haven’t seen any rabbits anywhere. I would not eat a rabbit. Don’t ask me any more questions.”

- Assuming the Bear ate the Rabbit, was it okay for the Bear to eat the Rabbit?

- How do you know if an action is just?

- Was this action just punishment for the Rabbit, assuming the Rabbit stole the Bear’s hat? Why or why not? What makes it justified?

- How else could the Bear have gotten back his hat?

- Is there a way to recover his hat without violence?

Punishment

- Are the Rabbit’s stealing of the hat and the Bear’s eating of the Rabbit equally bad? Why or why not? What makes one worse?

- If they are equally bad, does that mean the Bear should have the same punishment as the Rabbit? Why or why not?

- If not, what punishment does the bear deserve? What makes this punishment proper? Is it just?

- Do you think the Bear ate the Rabbit to get revenge?

- Is it okay for the Bear to eat the Rabbit as revenge for what the Rabbit did?

- Is revenge different than punishment? Why or why not?

- Does the intention the Rabbit’s action change whether or not the Bear’s eating it is acceptable?

- If the Rabbit didn’t steal the hat, was the Bear’s eating him proper punishment?

- If the Rabbit did steal the hat, was the Bear’s eating him proper punishment?

- Do you think two wrongs can make a right? Is the eating of the rabbit acceptable only if the rabbit stole the hat? Is the fact that one act is meant to respond equally to another what makes something just?

- Are lying. stealing, and killing equally wrong? Why or why not? Which is more wrong?

- In order to be just, can a punishment not be more wrong than the original crime?

- Is death a proper punishment for theft even if killing is worse than stealing?

- Is killing ever a just punishment?

Original questions and guidelines for philosophical discussion by Meredith Marshall and Yuwei Zheng. Edited June 2020 by The Janet Prindle Institute for Ethics.

Find tips for leading a philosophical discussion on our Resources page.