The Democratic party refrain of 2024 has been that democracy is on the ballot. Certainly, Trump’s actions have raised concerns from the events of January 6th to his continued denial of the results of the 2020 election (and refusal to commit to accepting future election results), to a recent controversial quote: “In four years, you don’t have to vote again. We’ll have it fixed so good, you’re not going to have to vote.” (Trump later provided some clarification.)

And yet the Democrats have hardly been maximalist about democracy this election. When Biden was his most stubborn during the nomination process, he asserted that the voters had spoken, despite the lack of a competitive primary. Later, when he stepped aside, Harris was advanced to the top of the ticket without a public referendum.

Of course, the spirit of Democrats’ rallying cry is not that this or that behavior is undemocratic, but rather that the former president represents an existential threat to American democracy. This raises a surprisingly challenging question: When does a democracy end? And how do we know?

We tend to speak of democracy in generalities: rule by the people, majoritarian rule, etc. Yet most modern democracies are a complex jumble of elements subject to varying levels of impact from the voting public. In the United States for example, senators and representatives are elected by the people (more democratic), whereas the president is selected through the electoral college (less democratic), and the Supreme Court is appointed (less democratic). It is worth noting that “democratic” is not always the same as good. Some notionally “less democratic” elements, such as courts, may be important safeguards for the protection of minority rights, as both Benjamin Rossi and I have previously discussed. The complexity of modern democracies hinders the ability to make simple, clear-cut distinctions and comparisons.

When evaluating failures of democracy, one strategy is to start with a minimal definition. The idea being that when these core features go, so does democracy. The conservative political theorist Joseph Schumpeter famously argued that democracy requires nothing more than competitive elections. Others have longer lists. For example, the theorist Robert Dahl enumerates six: elected officials; free, fair and frequent elections; freedom of expression; alternative sources of information; associational autonomy; and inclusive citizenship. According to Dahl these are the minimal political institutions required to achieve a functioning democracy. Even minimal approaches do not allow for a crisp delineation between democracy and non-democracy, for each criterion is complicated on its own. How should elected officials be elected? What is required for a fair election? Nonetheless, minimal accounts highlight common important features of democracies and we may be able to identify democratic failures even without a black and white distinction or single authoritative definition.

Alternatively, rather than looking for defining features, we can instead focus on what democracy is supposed to do. America is rather proud of its democratic history, but what makes democracy so great in the first place? Among numerous defenses, a classic approach is “instrumental defenses” of democracy. The idea is that democracy is good because it delivers good results, such as effective policy, economic growth, peaceful international relations with other democracies, and a civically engaged populace. From an instrumental perspective we can worry about the health of democracy – that is, the results it’s delivering – even if we think our democratic procedures are solid. We may think that there has been a democratic failure if a country elects to drastically limit civil rights, even if a majority of voters supported it. Less radically, we might also identify democratic failure with elected officials no longer being responsive to voters after they take office. Popular conceptions of democracy often incorporate features beyond political process, such as rights and liberties, but there can still be disagreement about what exactly a democracy is supposed to do. Nonetheless, considering what we want democracy to do can highlight key elements. For example, it may make sense to limit campaign spending, if we believe it accomplishes an important goal of democracy, like giving citizens with vastly differing personal wealth and power an equal stake in government. An implication of a result-oriented approach is that people may lose faith in democracy if it fails to deliver certain political outcomes.

Assuredly, some democratic failures are especially decisive: a party staging a coup with the help of the military, a president refusing to leave office after losing an election, officials banning a specific demographic from voting. In such cases, we can expect citizens to recognize that a major democratic failure has occurred. But consider the following two scenarios. In case one, an incumbent politician loses an election 48% to 52%, but nonetheless refuses to step down and pressures the judiciary to declare them victorious. In case two, through limiting the number of polling stations and controlling their location in unfavorable neighborhoods, an incumbent party wins an election 52% to 48%. Absent this manipulation of polling stations, they would have lost the election 48% to 52%. The democratic failure is more obvious in case one, but the effect is similar.

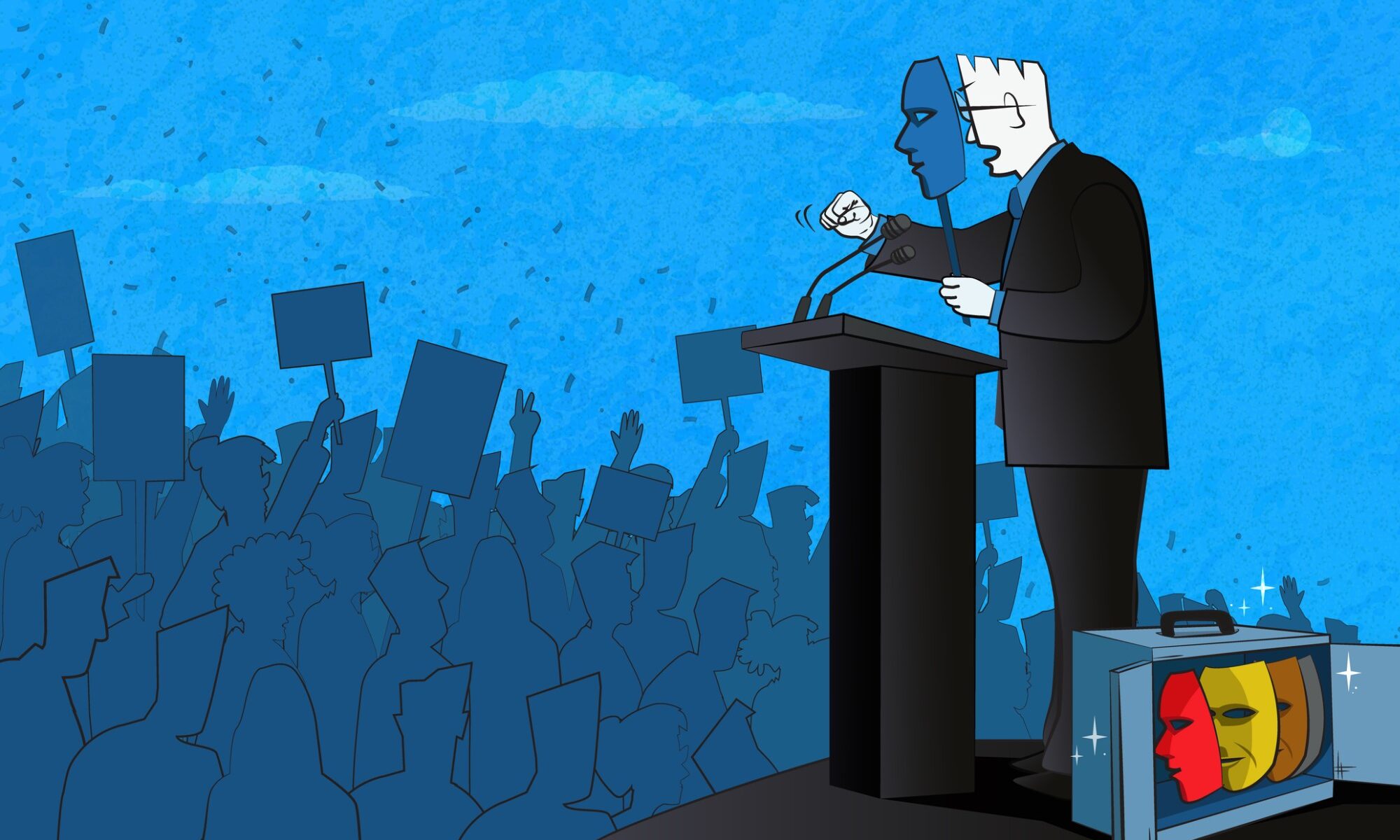

The worry is that if people expect certain signals for major democratic failures, they may fail to appreciate the less dramatic ones. Votes can be rigged, voters can be disenfranchised, voting power can be unfairly distributed, and real decision-making power can rest with unelected officials. The public quickly acclimates to less democratic approaches. The United States gladly considered itself democratic for much of its history, even while systematically denying voting rights to Black Americans, women, and the poor. It turns out that democratic lip service and actually democratic political practices come apart quite easily.

Today, Americans are extremely cynical about the state of their democracy. 72% say the U.S. is no longer a good example to follow. But we should not expect the death of democracy to look like just one thing. Voter suppression, gerrymandering, moneyed influence, or an overzealous Supreme Court can undermine democracy as assuredly as a coup. Guided or managed democracies, which maintain the superficial appearance of democracy, even while being largely beholden to an entrenched minority, may be as much of a threat as some extravagant collapse into totalitarianism. If anything, focusing on Trump as a singular threat to democracy interferes with a broader conversation about democratic failures and the ideal that American democracy should aspire towards.