The Cold Case of Alabama’s Embryos

On February 16th, in Burdick-Aysenne v. Center for Reproductive Medicine, the Supreme Court of Alabama in Montgomery decreed embryos created via IVF, consisting of roughly eight cells, and held in sub-zero storage by a fertility clinic, must be considered synonymous to children. Such a ruling has satisfied some and angered others, but above all (including myself) bamboozled most.

The facts of the case are remarkably straightforward, even if its consequences are not.

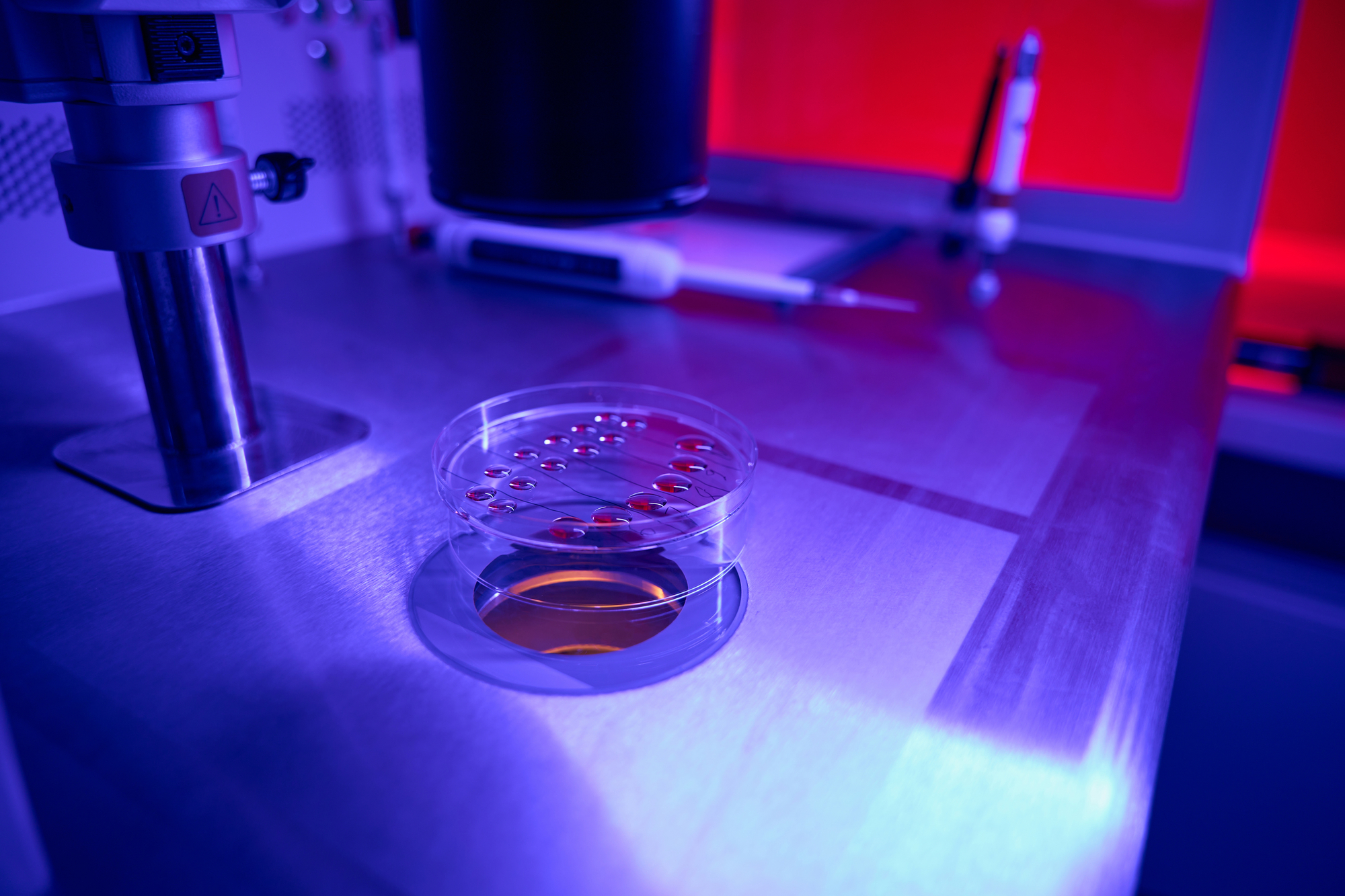

The plaintiffs are three couples who underwent IVF treatment at an Alabama-based fertility clinic. The IVF treatments resulted in not only healthy children for each couple but also several additional embryos. This is normal, as these additional embryos are made in case additional implantation attempts are needed or if the couple decides to have more children in the future. These surplus embryos were held in what was meant to be secure storage at the IVF clinic. However, a third party accessed the room where these, amongst other embryos, were stored. This person, for whatever reason, then grabbed the embryos, which, given that they were freezing, caused burns to that person’s hand. They then dropped the embryos, resulting in the latter’s destruction.

The plaintiffs brought the lawsuit against the fertility clinic under Alabama’s Wrongful Death of a Minor Act, arguing that the clinic’s negligence in allowing the third party to access the storage room resulted in the death of the plaintiffs’ “children.” The initial trial judge dismissed the case because embryos existing in vitro (outside a living organism) are neither children nor people. But, upon appeal, Alabama’s Supreme Court sided with the plaintiffs, asserting that the Wrongful Death of a Minor Act does apply because the embryos were, in fact, children. As Justice Mitchell writes in the ruling:

The central question presented in these consolidated appeals, which involves the death of embryos kept in a cryogenic nursery, is whether the Act contains an unwritten exception to that rule for extrauterine children – that is, unborn children who are located outside of a biological uterus at the time they are killed. Under existing black-letter law, the answer to that question is no: the Wrongful Death of a Minor Act applies to all unborn children, regardless of their location.

The consequences of this ruling have been significant. Two of the eight IVF clinics in Alabama have stopped offering their services as embryo damage or destruction is an ever-present risk during the IVF procedure. This ruling directly impacts all those potential patrons looking to start (or grow) their families. What’s more, it predominantly impacts those who have just enough money to afford IVF but not enough to use out-of-state providers.

Clearly, the ruling has some long-term pragmatic impacts which need ironing out: Does this mean that anyone currently holding embryos in storage is now expected to do so in perpetuity? What is to be done with these embryos if they are never implanted or cannot be implanted for medical, scientific, or financial reasons? If never-ending storage is required, this will inevitably drive up IVF costs, making fertility treatment even more inaccessible to Alabama’s poorest. And while this may sound like an absurd proposition, apparent absurdity is no legal defense if civil (or even criminal) charges are brought.

Now, the ethical issues associated with embryo, fetus, and gestating entities’ moral status is something which has been discussed and debated for centuries chiefly in the context of abortion, so I won’t rehash this debate here (but, for clarity’s sake, I don’t think embryos are children). Instead, what I believe is essential here, or at least what this ruling has thrust into the spotlight, is the effort to drive the concept of fetal personhood into realms in which it makes no sense for it to be deployed (if the idea even makes sense at all, that is).

I would have thought it would have been obvious to say that an embryo – a collection of biological matter of not more than eight cells – is not the same as a child. If done right, I can put an embryo into subzero temperatures without damaging it. This cannot be done with a child – freezing them will kill them. Also, the series of events that must happen, in a specific order at a specific time, for an embryo to become a child is long and uncertain. This is true in cases where IVF isn’t used, where fertilization, implantation, and gestation all take place over roughly nine months, and a myriad of cellular and extra-cellular events must happen in a specific order and particular way in order to produce a child. In IVF, all of this still needs to happen, with an added stage at the beginning where implantation requires scientific and medical assistance – you can’t just throw a frozen embryo at a prospective parent and expect things to turn out alright.

Beyond the disparities between a frozen embryo and a fully-fledged child, the ruling also stands on some shaky theoretical ground regarding the entities’ physical location – it’s not inside a person and thus not gestating. Even if one accepts that life begins at conception, they needn’t concede that all conception results in life. These frozen embryos exist outside a gestational environment and thus are not developing into a child or anything else. They are frozen in time; if they are not developing into children, why would we treat them as such? To have such a simplified idea of meaningful life and gestation, that once a sperm and egg fuse, that morally significant life begins, is to view such entities in stark contrast to the complex matrix in which all life, be that developing or developed, must exist. Simply having the raw ingredients for what might eventually become a child is not the same as having the child itself. Or, by way of a very clunky analogy, just because you’ve mixed some flour, butter, eggs, and sugar doesn’t mean you’ve got a cake; you still need kitchenware, an oven, and a power source to heat it. Without those, potentiality means nothing.

Ultimately, the case is bizarre (I haven’t even touched on using religious scripture as a jurisprudential foundation), and it can be easy to get bogged down in the ruling’s minutiae. But what I think is more important, and what I’m sure others have done in detail already, is to place this ruling in the context of the increasing rolling back of reproductive liberty within the U.S. With the Burdick-Aysenne v. Center for Reproductive Medicine ruling coming so soon after the overturning of Roe v. Wade by the Dobbs v. Jackson Women’s Health Organization case, it seems increasingly clear that women’s reproductive health and fundamental bodily freedoms are increasingly under threat. While this case is situated in the language of saving the life of the unborn (or even yet to be implanted), I cannot help but see it fitting into the canon of regressing reproductive liberties of the living and its ever-growing reach.