Information Deficits and Not Enough Civics Majors

It feels like it’s been a pretty bad year when it comes to people having a basic understanding of civics. Over the past few months, my home country of Canada has seen numerous reactions based on misunderstandings of how the government and legislative processes work. For example:

A proposed bill S-233 calls for research into the possibility of creating a guaranteed livable income program in Canada. In response, one former Ontario politician tweeted that the bill will deny access to social programs to anyone who hasn’t been vaccinated, and sitting Canadian Senators have reported receiving thousands of messages accusing them of being part of a sinister “New World Order” that is bent on enslaving humanity.

Lethbridge member of Parliament Rachael Thomas accused Justin Trudeau of being a dictator, based on a dictionary definition of “dictator” as someone who is “a ruler with total power over a country, especially one who has gained it using force.” This was in response to the Liberal and NDP parties forming a coalition government.

A Mississauga resident’s group claimed that the installation of a bike lane on a major road in their neighborhood constituted an infringement on their Charter rights, specifically Section 7, which guarantees fundamental rights to life, liberty, and security to all Canadians.

My neighbors to the south have also exhibited some less-than-stellar understanding of the consequences of newly passed and proposed laws. For instance, a proposed law in Maryland that sought to protect women from being prosecuted or sued for pregnancy loss, miscarriage, or abortion was misinterpreted by many anti-abortion and Christian conservative groups as essentially legalizing infanticide. This is, of course, not true.

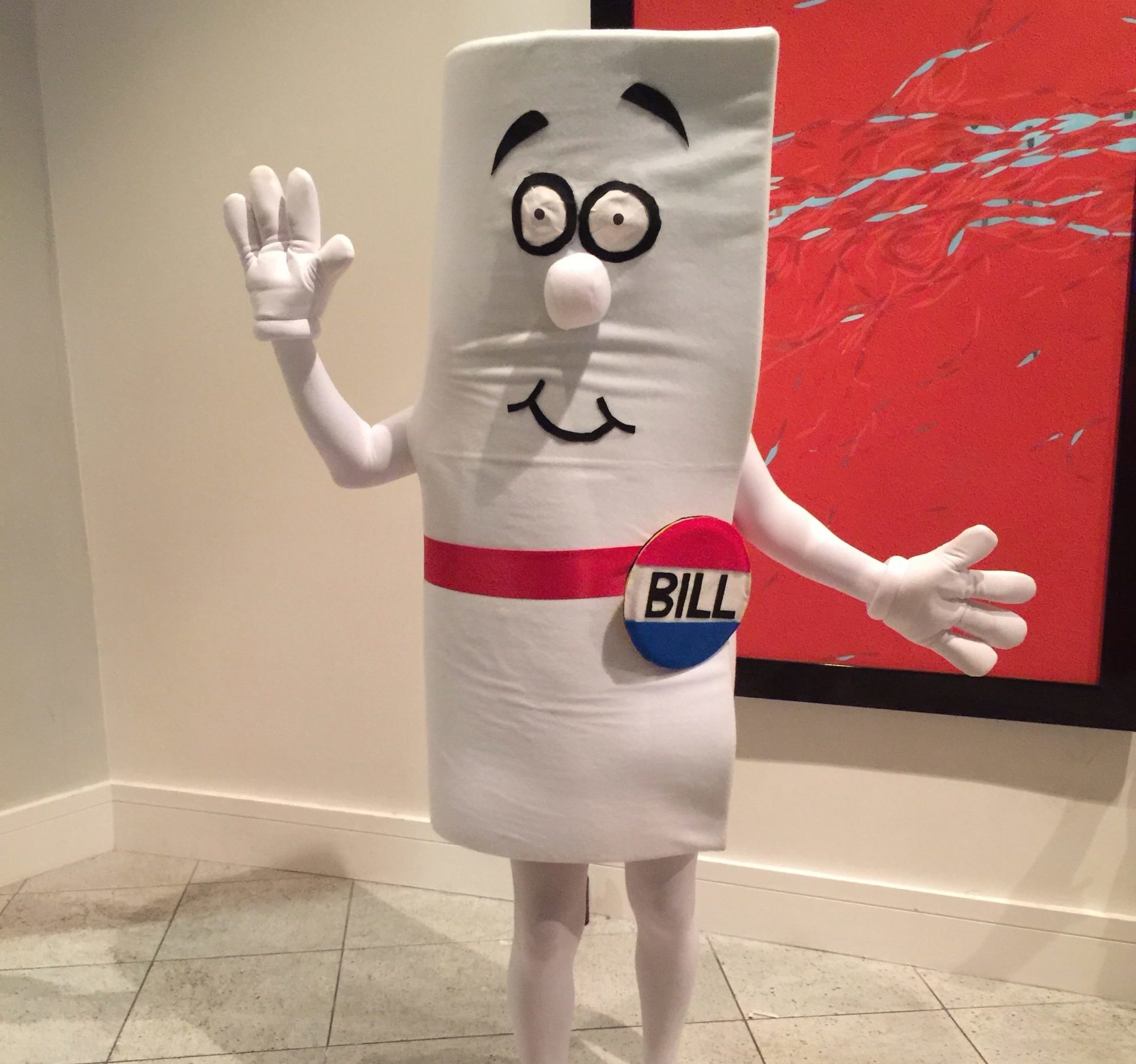

While there are many differences between these cases, they seem to share an underlying misunderstanding of some key concepts pertaining to how governments and laws function. Diagnosing the problem in Canada, one conspiracy theory researcher noted how many of the online discussions that fueled the above misunderstandings take place on “alternative platforms” – e.g., websites like LifeSite, in which much of the misinformation surrounding Bill S-233 has been circulated – which may end up acting like echo chambers, and in which gaps in knowledge “are easily filled with fantasy.” They summarized the situation as follows: “It’s easy to see a sinister plot when you don’t actually understand how the government works. These people aren’t civics majors.”

We’ve also seen that what’s at stake is not simply one’s ignorance: as the above cases illustrate, acting on the basis of poorly conceived notions of civics can lead to harm, especially if gaps in knowledge are filled in by unreliable sources of information.

We’ve certainly seen a lot of misunderstanding of science over the past couple of years, and we might think that gaps in scientific knowledge could also be “easily filled with fantasy” to produce the numerous conspiracy theories surrounding COVID-19 and vaccines that we’ve seen in that time. Perhaps there’s a similar problem going on in the above cases: if Canadians and Americans (and, presumably, citizens of other countries, as well) were more knowledgeable about how bills were passed, how dictators came to power, what rights citizens were guaranteed according to whichever documents guarantee them said rights, etc., then they would be less likely to reach false and fantastical conclusions about matters pertaining to civic matters.

This kind of explanation appeals to what is sometimes referred to as an “information deficit.” The idea is that – especially when it comes to scientific matters – what’s missing in cases where people are skeptical of received views, act in a hostile manner towards those who hold such views, or are distrustful of experts, is a lack of relevant information and knowledge. For example, according to this kind of explanation those who are skeptical of global warming may be so because they simply fail to know or understand climate science, and those who refuse vaccines are ignorant of how they work and that they are safe and effective. We saw above a similar information deficit model proposed when it comes to matters of civics. Ignorance of how to properly interpret a bill, as well as how bills become laws results in gaps.

Information deficits are intuitive, and suggest a clear solution: if the problem is ignorance, then the solution is education. If the problem is that “these people aren’t civics majors,” then the solution is perhaps to provide them with a more comprehensive civics education.

While it’s certainly not a bad thing to try to provide people with knowledge to fill in any gaps, research suggests that at least when it comes to scientific matters, scientific ignorance is not what matters most. There is ample evidence that merely providing more information does not increase public trust in science, nor does it result in greater acceptance of consensus scientific views.

One major criticism of only addressing information deficits when it comes to scientific beliefs is that filling in gaps in knowledge is typically a one-way interaction, where experts provide information and laypersons are meant to believe it. When it comes to politicized and contentious issues especially, simply providing information to be believed does not generally help to change one’s mind. More effective, perhaps, are models that encourage interactions between experts and non-experts: “public engagement” models of science communication, for example, emphasize dialogue and non-expert participation in scientific forums, and there is evidence that these kinds of activities increase overall trust in science.

When it comes to matters of civics, it seems similarly unlikely that merely providing more information about how governments function will solve problems like those mentioned above. While it’s tempting to think that if people had paid more attention in civics class then we wouldn’t have the problems surrounding the misinterpretation of laws, rights, and accusations of dictatorships, solely addressing knowledge gaps is likely not the best way forward.