Biden, Trump, and the Dangers of Value-Free Science

I don’t think it’s controversial to say that the Trump administration lived in tension with scientific advisors. Because of concerns that Trump politicized science in ways that put life at risk and undermined public trust, the Biden administration is launching a 46-person federal scientific integrity task force to investigate areas where partisanship interfered with scientific decision-making and to come up with ways to keep politics out of science in the future. While risk to scientific integrity is an important concern, the thinking behind this task force risks covering up a problem rather than resolving it.

Critics seeking “evidence-based policy-making” have accused the Trump administration of letting politics interfere with issues including, but not limited to, coronavirus, climate change, and whether Hurricane Dorian threatened Alabama. They also argue that this interference made the response to COVID-19 worse and led to a higher death toll. Jane Lubchenco, deputy director for climate and environment at the White House Office of Science and Technology Policy, noted, “What we have seen in the last administration is that the suppression of science, the reassignment of scientists, the distortion of scientific information around climate change was not only destructive but counterproductive and really problematic.”

But it isn’t clear scientific integrity can be defined in a way that is free from political interference or that it should be. Consider the memo from Biden on the subject which states that “scientific findings should never be distorted and influenced by political considerations.” While this might mean making sure that findings and data are not suppressed or distorted in ad hoc and arbitrary ways, this approach also sounds like an attempt to enforce a value-free ideal of science, which, according to many philosophers of science and scientists themselves, is neither possible nor desirable.

For starters, it isn’t clear that we can completely separate politics from science even if we wanted to. According to philosopher Helen Longino, what we take as evidence for something requires assumptions that are informed by our values. These assumptions often cannot be (and are not) empirically measured, and so “there are no formal rules, guidelines, or processes that can guarantee that social values will not permeate evidential relations.” Such assumptions can dramatically affect the methods taken by scientists including what protocols to follow, what sorts of things to measure, and for how long.

For example, in his book A Tapestry of Values, Keven Elliot provides an example of Woburn Massachusetts in the 1970s when several people became ill and it was noted that the local water had taken on a strange color and taste. Eventually it was discovered that barrels of industrial chemicals were found buried near the city’s wells. Proving a direct link between these chemicals and the many cancers and illnesses in the city proved difficult. A department of public health report about a connection between the two was inconclusive. Later, citizens of the community managed to get a separate study commissioned with significantly more input from the community and which later found that there was a significant correlation between consumption of water from the contaminated wells and the health problems people experienced. As Elliot notes,

“assumptions about the appropriate boundaries of the geographical area to be studied can be very important to scrutinize; if a study incorporates some heavily polluted areas and other areas that are not very polluted, it can make pollution threats appear less serious than they would otherwise be. Similarly, analyzing health effects together for two neighboring towns might yield statistically significant evidence for health problems, whereas analyzing health effects in the two towns separately might not yield statistically significant results.”

In other words, there are many cases where values are needed to inform the methods of research that is taken.

Consider an example from the headlines this week. On Monday it was reported that less than 3% of all land on Earth is fully ecologically intact. Philosophers Kristen Intemann and Inmaculada de Melo-Martin have argued that measuring climate impacts requires values because “impact” depends on judgments about what is worth protecting. As the paper that inspired this week’s headline makes clear, “there is no clear definition of what is meant by intactness and the term is used loosely in the scientific literature.” For some scientists measuring the intactness of an ecosystem is done by measuring anthropogenic influence, whereas for the authors of the paper measuring whether an ecosystem is intact will involve measuring the habitat intactness, faunal intactness, and functional intactness. Depending on how this is measured, we find that the amount of land that is intact varies from 3% to 25%. The decision regarding which of these measures to use is quite significant and will inevitably depend on our values. Whatever we decide, the findings will have an enormous impact on our policies.

Philip Kitcher has argued that science is not just about finding truth, but finding truths we deem significant, which makes democratically-informed values highly desirable. The decision of whether agricultural science should focus on efficiency and maximizing crop yields or sustainability and maintaining future output is something that we might want to be politically-informed. Another area where values are desirable involves cases of inductive risk. As I’ve previously explained it, inductive risk involves cases of dealing with the risks of real world consequences relative to the uncertainty you have in your current conclusion.

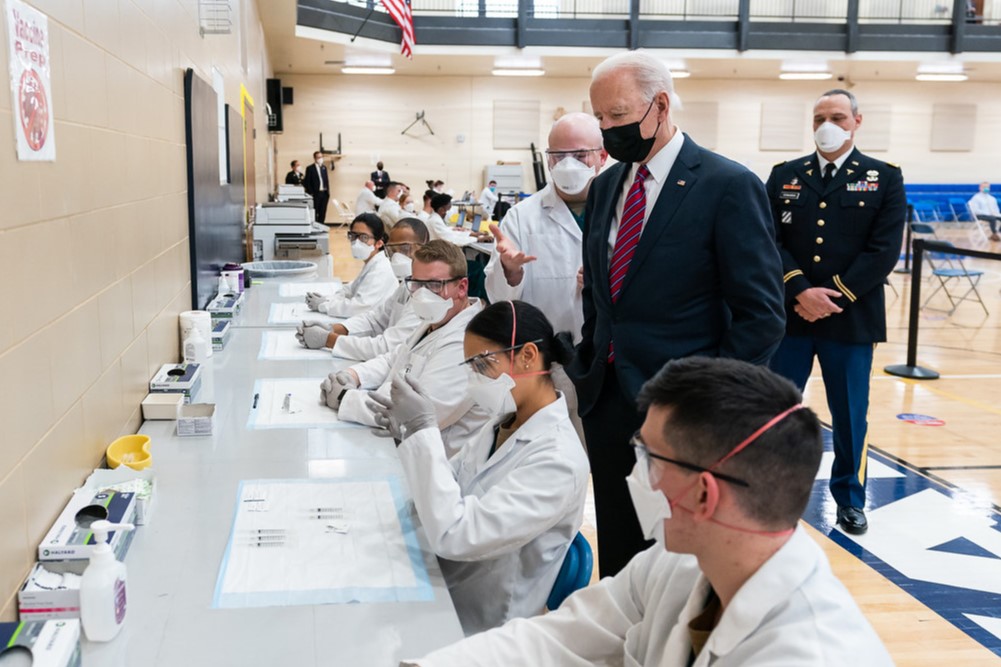

A really good example of this thinking at play is the public health advice when it comes to COVID. From social distancing, to mask-wearing, to vaccine use, the guidance has always been a matter of weighing what is known relative to risks of being wrong. This has been pretty blatant. Experts need to weigh the risks of, for example, using the AstraZeneca vaccine despite not knowing a lot about its connection to blood clots because the alternatives are worse. In a case like this, regardless about how you may feel about the scientific findings, when scientists say the benefits outweigh the risks, this is a value judgment, and therefore it is a fair question whether political or ethical values other than those of scientists should be relevant to science in way that doesn’t damage the integrity of the research.

For these reasons, many philosophers have argued that trying to bury values under the rug and pursuing a goal like value-free science isn’t helpful. If, in your attempt to banish political interference, values are only made more subtle and difficult to notice, you only make the problem worse. It’s possible that efforts to secure scientific integrity may stop short of the value-free ideal; the aim may not be to weed out all values, but only “improper political influence.” But then the word “improper” takes on huge significance and requires a lot of clarification. Thus, there is a larger moral question about how much influence democratic values should have over science and whether it is possible to provide an account of integrity that may be politically informed but not just as politically controversial at the end of the day.