Censoring Richard Wagner

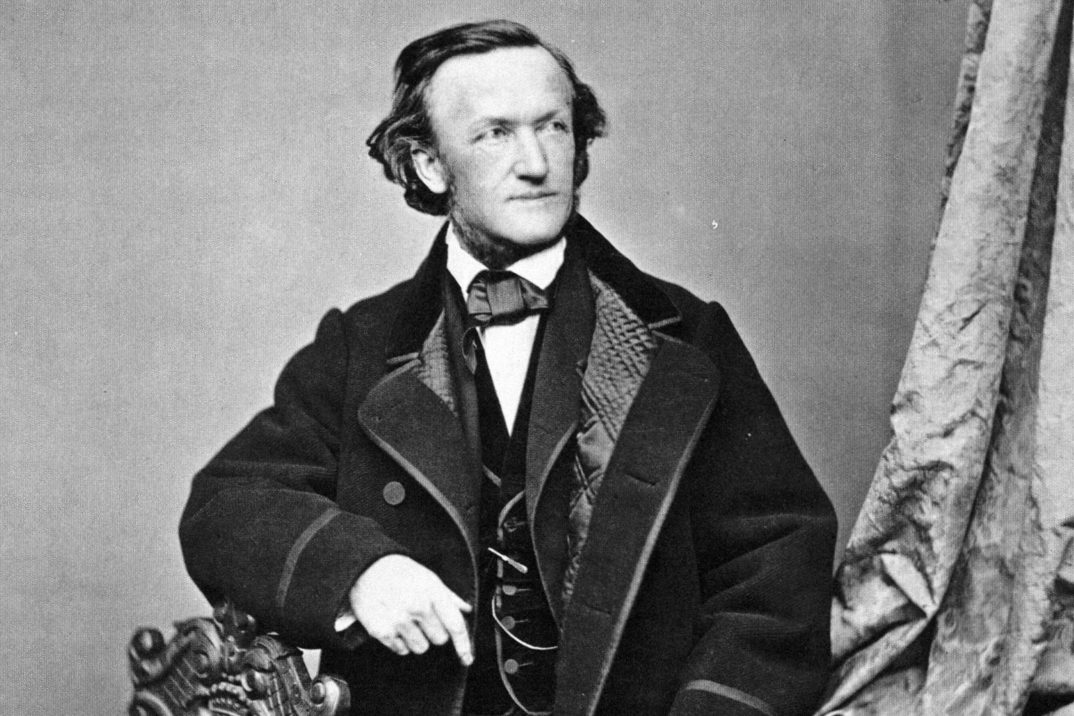

The Romantic Era of music brought us some of the most beloved minds in Western music we have ever known. Beethoven, Verdi, Puccini, Chopin – the list could go on and on. Following Beethoven’s brilliant instrumental music legacy, however, one German composer’s ingenuity stood out above the rest – Richard Wagner. While he was alive, Wagner was the single most popular composer in Germany. Even today, Wagner is one of the most celebrated composers in all of Western music history, and his operas are still performed worldwide. Unfortunately, however, his legacy has been tarnished by his radical anti-Semitic beliefs which were translated into many of his operas. Questions about the ethicality of performing his art in a modern setting have long been debated by the classical music community.

In order to tackle these questions, understanding Wagner’s cultural and personal background is necessary. Richard Wagner lived in 19th century German-speaking Central Europe and composed his operas in the mid- to late-Romantic period. Wagner’s lifetime saw several political revolutions attempting to unify Germany. Those in favor of unification, including Wagner, took immense pride in their German roots. In reflection of this, many of Wagner’s operas were inspired by classic German legends and folklore. The devotion to German nationalism and call for unification caused many to question what exactly qualified someone to be considered German. Wagner’s answer did not include Jews. In 1850, Wagner published an essay entitled Das Judenthum in der Musik (Judaism in Music) which argued that music written by Jewish composers was inauthentic because its composers lacked national roots. The essay specifically targeted Jewish composers Meyerbeer and Felix Mendelssohn, who were widely popular in Germany during Wagner’s lifetime. As his operas reflected his highly nationalistic beliefs, so too did his operas reflect his conspicuous anti-Semitism.

The starkest example of these beliefs is found in his 1868 opera Die Meistersinger von Nürnberg. The opera centers around a singing competition, in which the grand prize is the town poet’s daughter’s hand in marriage. Beckmesser, one of the contestants, is portrayed as a foolish laughingstock, his role wrought with racially-charged Jewish stereotypes. In the final scene of the four-and-a-half hour opera, Beckmesser butchers his last song of the contest and is humiliated and laughed off the stage. After the winner is crowned, the town poet sings a final aria about the supremacy of German art, and warns the townspeople about the threat foreigners pose to German society.

The anti-Semitism in Wagner’s works was brought to light in World War II-era Nazi Germany. Adolf Hitler became enamored by Wagner’s music when he was just twelve years old. Fifty years after Wagner’s death, Hitler became chancellor of Germany. Hitler effectively put Wagner’s music on a pedestal as a representation of true national German art and brilliance. He frequently played Wagner’s music at Nazi events, and used the annual Bayreuth festival’s celebration of Wagner as a massive propaganda ploy for the German people.

Today, Wagner’s legacy is marred due to his operas’ anti-Semitic themes and characters, and especially for its use in Nazi propaganda. Still, his music is undeniably genius, and is enjoyed by many. The fact remains that Wagner was dead long before Hitler was even born, so he had no say in whether or not his music was used as Nazi propaganda. Even so, the content of his operas has proven to be quite problematic.

Music directors have long struggled with how to attack the anti-Semitic parts of his operas. Israel has completely banned his music for decades, though to stop performing his operas entirely would be heartbreaking, as his musical genius and popularity is undebatable. One possible solution to Meistersinger, offered by David McVicar of Glyndebourne Opera Festival in England, is to introduce Beckmesser as a well-respected equal in the town rather than a villainous schemer. This raises the ethical question of whether or not altering potentially offensive or controversial art to ease audiences is in fact a form of censorship. At what point does sugarcoating cross over into censorship? If McVicar’s solution is considered censorship, are there other ways to present the art in a non-offensive manner? Or is allowing audiences to see the art in its intended fashion and to interpret it in their own way a part of the learning process in moving away from racist ideologies?

This also raises the dilemma of whether or not an artist’s personal beliefs can be separate from his or her art. Are all of Wagner’s works inherently bad because he was an anti-Semite? Rachel Cooke of the Guardian argues that our inability separate an artist’s personal life from their art actually “robs us […] of so much that is good and beautiful.” For the sake of discussion, one could also argue that understanding the cultural or personal context behind why and how an artist creates their art is an essential part of understanding the art itself.

These questions are applicable to all disciplines of art as well. If we only look at art as reflections of an artist’s objectionable beliefs, we run the risk of losing the work all together. Yet if we separate the art from the cultural context from which the artist created their work, we lose important context in understanding the piece. If a topic is objectionable, directors and administrators must consider ways to make it less so, without crossing the line into censorship.